Founding fathers of NFL instant replay scared where it's headed

On a brisk December day at the Meadowlands – 20 years and one month before a blown call so blatant and so harmful that it almost single-handedly rewrote an NFL rule – Vinny Testaverde bolted through an unsuspecting defensive line and presented the league with its 1990s Rams-Saints equivalent.

It was fourth-and-goal from the 5. Twenty-seven seconds remained in a Week 14 game between the New York Jets and Seattle Seahawks. Seattle’s 1998 playoff hopes hung in the North Jersey air. With the Jets down five, Testaverde lunged. His knee scraped turf. The ball was a half-yard short. And madness ensued.

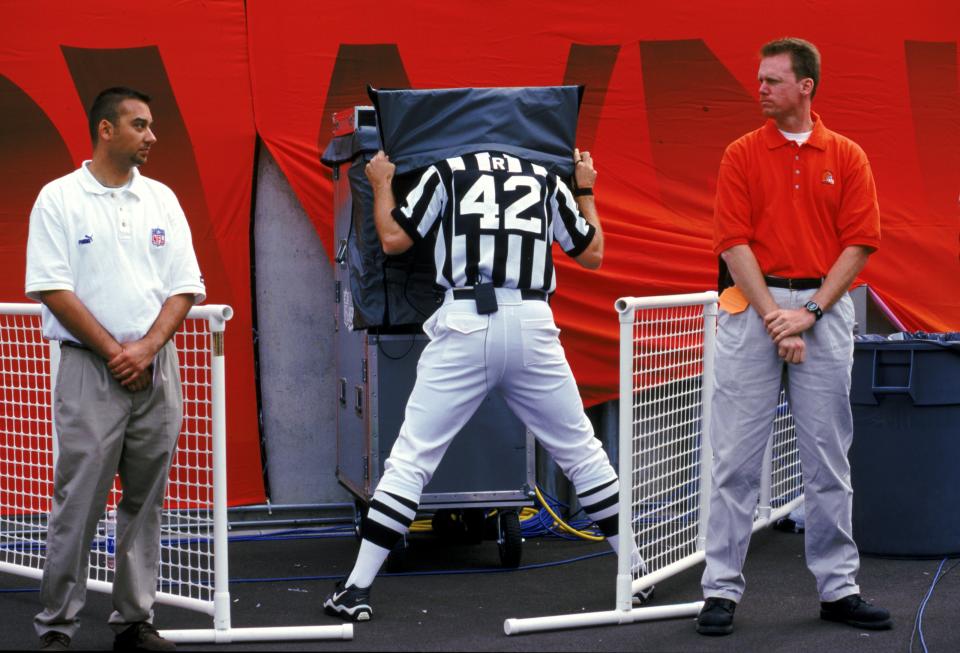

Eleven Jets, 10 Seahawks and six referees converged on a 4x4 patch of fake grass. Uncertainty reigned. Officials contradicted each other, then conferred. Mere seconds after their hands shot up in the air, signaling touchdown, CBS cut to a replay that made broadcaster Kevin Harlan exclaim: “He didn’t get across … No, not even close! Not even close!”

And the NFL, in its seventh season since scrapping Instant Replay, Vol. 1, could do nothing about the injustice.

The following morning, the controversy screamed off the front page of the New York Times. The following month, Seattle had missed the playoffs by one game; head coach Dennis Erickson had been fired. The following offseason, something had to change. And it did.

Twenty years later, members of the late-90s competition committee and league office remember the Testaverde play as the “tipping point.” As the “catalyst.” In a way, analogous to Rams-Saints. The following fall, instant replay was reimplemented in the NFL. This time, it was here to stay.

Twenty years later, those same members also say it has served its purpose. Which was, as former NFL vice president of officiating Dean Blandino says, “to correct the obvious error in a critical situation.” And has it made the NFL better?

“I think the answer to that,” former commissioner Paul Tagliabue says, “is certainly yes.”

“Because,” adds competition committee chairman Rich McKay, “you never want the audience to not have faith in the way the game is played, and the integrity of the game. I think replay gives people that faith.”

But with its 20th birthday approaching, it also has those same founding fathers concerned. “Worried.” Even “scared.”

[Best to worst: Ranking the replay systems in sports]

In March, NFL team owners voted 31-1 to adopt a rule that will make pass interference reviewable. It is, Blandino says, “such a huge departure from where the league and the competition committee has been. The system was put in place to deal with objective facts. The ball hit the ground, the foot stepped out of bounds, the ball broke the plane of the goal line. And this is the first shift of that philosophy.”

Blandino feels it’s the NFL’s biggest rule chance since ’99. Because it’s replay’s first true venture into the world of subjectivity.

“And you don’t want to go there,” says former Colts president Bill Polian, who was on the late-90s competition committee that brought replay back to the league. “Crossing that line into a judgement call, to me, is a line that we should not have crossed.”

“And I am scared to the dickens … I’m worried about it, to be honest. Because the history,” Polian says of the past two decades, “is of replay creep.”

In other words, a gradual shift towards an unintended commitment.

Fearing the future

Fifty guys at a bar. That was the hypothetical the late-90s competition committee used to consider instant replay. It became the metaphorical standard, the threshold for a reversal. Only when “everybody, all those 50 agree that that play should be reversed,” should a call be overturned, McKay remembers.

His colleagues had been scarred by the NFL’s ill-fated first replay experiment. From 1986-1991, all stoppages came from the booth. Some games featured double-digit reviews. The system was unchecked, insufficiently accurate, disruptive and scrapped in ’92.

So when the debate picked back up later that decade, many involved were wary. Bengals owner Mike Brown and former Giants GM George Young led the anti-replay camp. And Young, according to others involved in the discussions, had a prescient concern: “We have a system that we want to put in place,” Blandino says, paraphrasing the late executive. “But we have no way to prevent it from expanding beyond what we initially intended it to be because of where technology’s gonna go.”

Whether replay’s pioneers knew so, their groundbreaking proposal in 1999 wasn’t merely a contemporary measure. It was a gateway to a broader, more powerful system. Accounts differ on how much that prospect loomed over their discussions. But it was seemingly present.

“Some people voted no on that exact argument,” recalls McKay, a competition committee member since 1994. “‘Hey, technology’s going to get better, it’s going to force us to expand replay, and therefore we should never put replay in. It will get too unruly.’”

“I remember a lot of people who were anti-replay bringing that up,” Blandino confirms. “ ‘OK, we’re trying to keep this system limited, but as technology gets better, it’s going to be very difficult to maintain the system as is. It’s gonna grow, and it’s going to expand.’

“And that’s exactly what’s happened.”

Technology – high-definition pictures, more cameras, zoom lenses, expeditious procedures – isn’t simply an enabler of replay expansion. It’s a driver. “Technology was evolving,” Tagliabue explains. “As the technology got better, and the picture got better, the public was seeing a lot of things that people realized we have to see. … The fans had more and more of an expectation that there should be some way to use this in officiating.”

“And then,” Polian says, “like everything else in life, mission creep came along. Replay creep took place. And all of a sudden, we got mandatory reviews of every scoring play and every turnover.”

For two decades, the NFL’s replay system incrementally branched out. More call types became challengeable. More play types were deemed consequential enough for automatic booth review. “Just like we were a little concerned about,” McKay says, “it’s probably gone beyond what it was initially intended to be.”

As the scope widened, reviews became a more common occurrence. The 1999 season brought 0.79 per game. That number had ballooned to 1.71 by 2014.

But it has nestled in at a four-year average of 1.50 since. Average game length, according to data obtained from the NFL, was actually shorter in 2018 than in 2000. The system is as efficient and as accurate as ever. “Instant replay,” McKay said in March, “is a tool that has served us very well.”

In other words, it has worked. It has righted obvious wrongs – until this past January, that is, when it couldn’t right the most obvious and costly wrong of all.

Until 2019, NFL lawmakers had, more or less, confined replay to objectivity. “When we created [the system],” Polian remembers, “we said, ‘We will never review judgement calls.’ ”

But the non-pass interference call in the NFC championship game and the uproar that stemmed from it pushed the league across the line. Subjectivity wooed it.

“And when you get into the world of subjective, there’s no way 50 people at a bar are going to agree,” McKay says. “It’s somebody’s judgement vs. somebody else’s judgement. And that’s an interesting area.”

It’s not necessarily a harmful one. The threshold for overturning pass interference calls and non-calls, at least in preseason, has been high. But “the creep of replay,” McKay says, “still does scare me a little bit.”

“Once we stray from correcting the obvious and egregious errors,” Polian explains, “and get into correcting judgement calls, we’re going down a really slippery slope.”

Is the new rule an overreaction?

So what if, four months from now, in the fourth quarter of a tight NFC championship game, an erroneous roughing the passer call changes the outcome? What if holding does similarly a year later?

“It’s a common-sense, obvious concern,” Blandino says. “Everyone’s gonna say, ‘Well, you can review pass interference, why can’t you review that?’ So we add roughing the passer. And then the next year we add holding. Last year, there were two false starts missed on touchdown plays that were impactful. Are you going to start reviewing false starts?”

The worry is that replay becomes cumbersome. Though most NFL coaches and executives support it, some, like Polian, believe it already has overstepped its bounds. And while public pressure has spurred replay forward, some fans complain that lengthy reviews interrupt the sport’s flow.

McKay, the president and CEO of the Atlanta Falcons, sees those complaints in survey responses. “You can’t believe how many times they talk about stoppage of the game, and how disruptive it is to them,” he says of Atlantans. “There’s no question you see pushback from the fans.” And without fans, as Falcons owner Arthur Blank likes to say to him, “we have 22 guys playing sandlot football.”

The use of replay, therefore, becomes a balancing act, serving diverse populations with diverse, often conflicting interests. Officiating perfection is desirable. But how hard do you chase perfection knowing it isn’t attainable? At what point do the marginal costs of yet another replay expansion outweigh the marginal benefits?

Or, as Polian puts it: “Is the incremental gain worth the pain?”

Some believe pass interference reviews will tiptoe dangerously close to the inflection point. Whatever comes next could surpass it. “There’s no question that that discussion of further expansion will continue,” McKay says. Replay’s “role in the penalty world,” he says, is the next frontier.

That the chairman of the competition committee is aware of the concerns should assuage some of them. So should the challenge system, which has kept replay in check for 20 years.

Still, those responsible for bringing it to the NFL are uneasy.

Says Blandino, now an officiating analyst for Fox: “I don’t think I would’ve went this route. I’ve never felt that changing a rule to fix one situation that happens every however many years – I don’t think you end up with good rules that way.”

And Charley Casserly, former Redskins GM and competition committee member, current NFL Network analyst: “I think the system has worked. But this is one I would’ve voted against.”

And Polian, the harshest critic of the bunch: “The original second incarnation of replay was a big success. But it’s gone downhill since. … There’s a whole new generation of people in the league who don’t remember the ills of instant replay.

“It is now open season on judgement calls,” he concludes. “And in my view, that’s a bad place to be.”

More from Yahoo Sports:

Cowboys reportedly making Zeke highest-paid RB in NFL history

Report: Rams, Goff finalize $134M extension w/ record guarantee

Mets outdo themselves, blow six-run lead in ninth vs. Nationals

– – – – – – –

Henry Bushnell is a features writer for Yahoo Sports. Have a tip? Question? Comment? Email him at henrydbushnell@gmail.com, or follow him on Twitter @HenryBushnell, and on Facebook.