Forever an owner's league: why NFL superstars are never truly free

Football’s best players can’t chase titles in the same way that NBA players do – not if they also want to get paid what they are worth

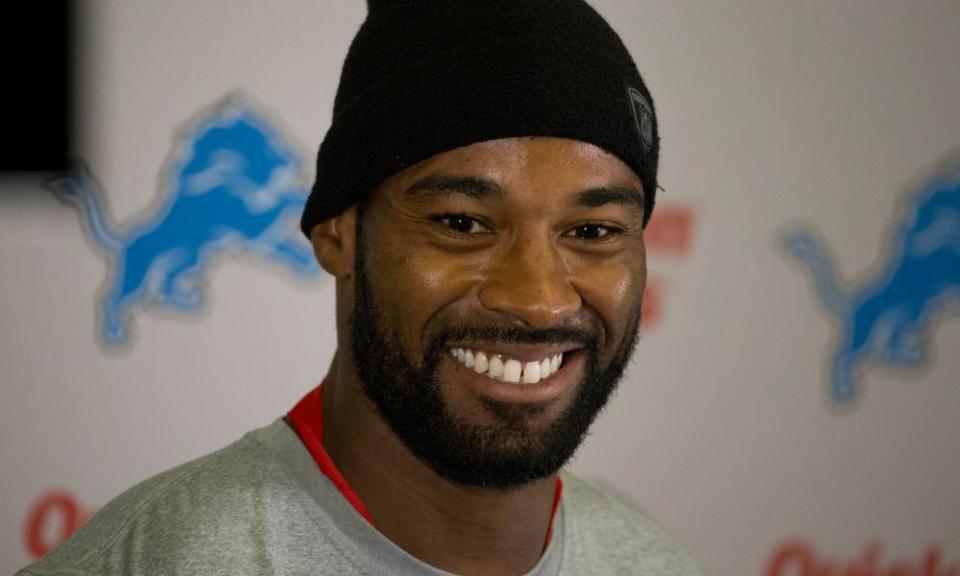

The former Detroit Lions star receiver Calvin Johnson has come to understand something in his retirement that thousands of current and former players have already learned. The NFL is an owners’ league.

Last week Johnson lamented his inability to jump ship to a football dynasty the way the NBA superstars LeBron James and Kevin Durant were able to do with the Miami Heat, Cleveland Cavaliers and Golden State Warriors. He decried the unfairness of enduring losing while not having the power to get himself to the Patriots or Broncos or some other championship-ready franchise.

“I was stuck in my contract with Detroit and they told me they would not release my contract, so I would have go come back to them,” said Johnson, who retired last year at 31 while still in his prime. “I didn’t see the chance for them to win a Super Bowl at the time and for the work I was putting in, it wasn’t worth my time to keep on beating my head against the wall and not getting anywhere. It’s the definition of insanity.”

Football has always been unfair to the men who break their bodies for the sake of Sunday glory. The price players like Johnson pay for sprinting down the sideline and leaping into a flying shoulder of a torpedoing defensive back is a lifetime of chronic, neck and joint pain to say nothing of loss of cognitive function. You can always spot a retired football player at a sports event: he’s the one with the barrel chest and the wobbly gait, as if his legs have curdled into oatmeal.

For much of Johnson’s time with the Lions he put up Hall of Fame statistics for a franchise that was the league’s standard for heartbreak. While Detroit eventually built themselves into playoff contenders they did so with a young quarterback still learning the NFL and a powerful but undisciplined defensive front. The only way Johnson was going to hold a Super Bowl trophy was if he snatched it from Bill Belichick’s hands.

From the sounds of his comments he would have rather gone to New England and played for Belichick instead.

The thing is, New England owner Robert Kraft wouldn’t want a system where Johnson would have signed a $100m contract and teamed with Tom Brady in an offense for the ages. Football is a sport where coaches demand control which traditionally has made players compliant, perpetually in fear of being cut either for performance or injury. The league’s concrete salary cap lacks the veteran exemptions and luxury tax options you see in other sports because the owners do not want to be trapped into overloaded contracts, with players whose careers are cut short by injury far more often than their counterparts in the NBA or MLB. Player deals are almost never guaranteed and the partial guarantees they receive count against the salary cap for the life of his contract, even if the player has long been released.

Johnson was actually lucky: a have on a team of have-nots. The eight-year $132m deal he signed in 2012 (a year before he was to become a free agent) guaranteed him $60m. There’s no way would Belichick, for instance, would give such a contract to a receiver when Brady already had a four-year $72m contract. The Patriots wouldn’t have had money to sign anyone else of significance.

Players have long grumbled about their lack of control but they have always accepted it. “You aren’t going to have guaranteed contracts in a contact sport,” one NFC East’s team representative to the NFL Players Association told me a few years ago.

It’s an attitude that has always marked the players’ dealings with the owners. Seahawks cornerback Richard Sherman recently said “players have to be willing to strike” to gain the kind of powers Johnson wished to have. And yet the players have always backed down in their labor battles with the owners, fearing the system would wash them out, filling locker rooms with willing replacements happy to take low (for pro sportsmen) wages for the chance to play professional football.

The best hope Johnson or Sherman or any other player has in gaining any measure of freedom from the NFL is to sue. This is the only way the players have won anything from the league. Gene Upshaw, the former head of the players’ association, loved to talk about the lawsuit built around running back Freeman McNeil that eventually won the players free agency in 1992, saying it was the only way to break the owners’ grip on players’ careers.

Upshaw once told Bob St John, the biographer of powerful Dallas Cowboys owner Tex Schramm, that Schramm told him during the 1987 players’ strike that the union would never win free agency. “Don’t you see? You’re the cattle, we’re the ranchers,” Upshaw said quoting Schramm.

In explaining the union’s aggressive litigiousness, Upshaw told me in 2007, a year before his death: “We have a duty to protect our rights and defend our player rights.”

Johnson had another right. He had the right to walk away from a failing team halfway through a $132m contract. On Monday, the Lions invited Johnson to training camp, possibly in the hope he might want to play again, especially after Detroit squeaked into the playoffs for the second time in four years – a dynasty by Lions standards. If he does want to be on the field again that will be his best chance. Who knows if he does? What he won’t be doing is getting together with a handful of great players and building a dream team. The NFL isn’t built for that.

Johnson is right. Football superstars can’t chase the rings – not if they also want to get paid what they are worth. It goes against our very nature to see someone quit because he can’t get himself to a better situation. But that’s the NFL.

Forever an owners’ league.