Fight Night at The Joe: 'Darren McCarty will never pay for a meal in this town again'

This is an excerpt from “Stanleytown 25 Years Later: The Inside Story of How the Stanley Cup Returned to the Motor City After 41 Frustrating Seasons” by the Detroit Free Press.

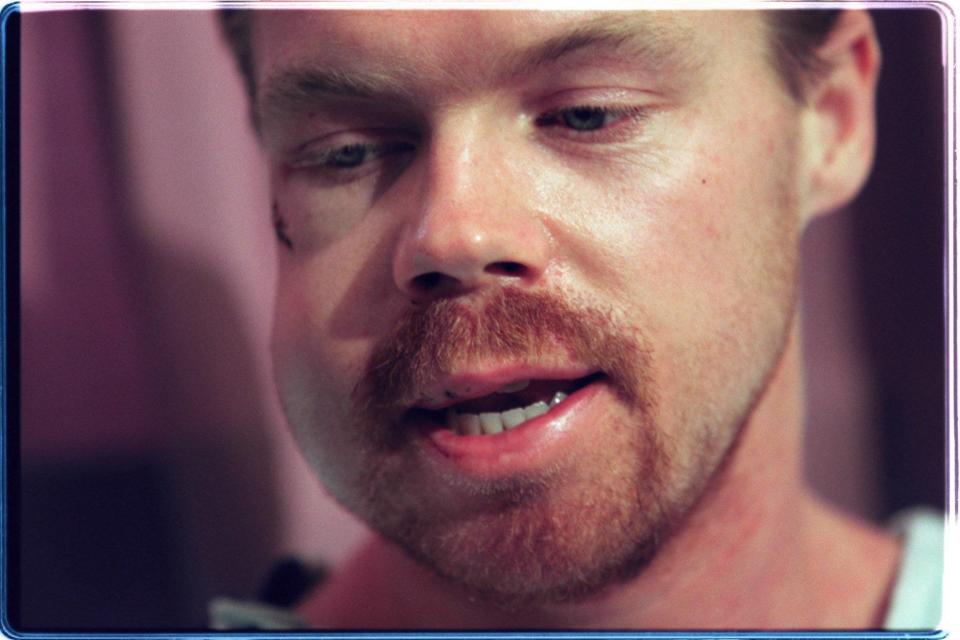

Darren McCarty will never pay for a meal in this town again. In two explosive moments that embody all that is right with hockey and all that is wrong with it, McCarty made an unforgettable impression on this Detroit Red Wings season. In the first moment, he bloodied the game. In the second, he won it.

— Mitch Albom, writing for the Detroit Free Press on March 26, 1997

FIGHT NIGHT AT THE JOE

There was a hockey game to be played, to be won on this wild and electric night. But the Red Wings took care of some old business first.

Three hundred and one days after Claude Lemieux’s cheap shot on Kris Draper, the Wings punched back. Their epic, contentious night of March 26, 1997, at Joe Louis Arena, highlighted by Darren McCarty when he pounded Lemieux into submission, solidified a sense of unity and confidence that carried them into and throughout the playoffs. The Wings conquered their biggest obstacle — doubt — when they vanquished the hated Colorado Avalanche.

“I guess it was a payback,” McCarty said afterward. “An opportunity presented itself, and something happened.”

[ I watched ESPN's 'Unrivaled' on Red Wings-Avalanche: Here's what I think. ]

Between the fights and pileups, when there wasn’t blood on the ice and goalies exchanging blows in the neutral zone, on the rare occasions there wasn’t chaos, there was hockey.

It was in those moments that the Wings showed they could beat — as well as beat up — the defending Stanley Cup champions. The Wings showed guts, skill and an undying resilience, erasing a two-goal third-period deficit for an improbable 6-5 overtime victory.

In Gordie Howe’s day they called it hockey. Now they called it “old-time hockey.” And this year marks the 25th anniversary of one of the most incredible sporting events in Michigan’s history.

“It’s a great rivalry, isn’t it,” McCarty said that night. “Man, that was fun hockey. … That’s one to remember. We stuck together in all aspects of our game.”

“Bloody good” blared the giant headline on the front of the Free Press Sports section, above a large picture of Colorado goalie Patrick Roy with blood streaks crisscrossing his face.

In Denver, the Post screamed “Bloody Wednesday!” And the Rocky Mountain News declared “Wings even score on Avs.”

[ Ref from Wings-Avs brawl reveals why Darren McCarty stayed in game: 'Paybacks are a bitch' ]

The night turned out to be so emotional, so violent and so dramatic that Red Wings fans universally rated it as the most memorable in the 38-year history of Joe Louis Arena or the second-most memorable, rivaled only by the June night less than three months later when the team ended its 42-year Stanley Cup drought.

A DASTARDLY DEED

Fans in Detroit waited for (this) game the way teenagers wait for the next “Nightmare on Elm Street” to open. They wanted revenge for the bloody night last season when Lemieux cheap-shotted Kris Draper into the boards.

— Mitch Albom

Thirty-nine penalties were handed out by exhausted officials, who raced from pileup to pileup like firefighters trying to contain a wildfire. The kindling had smoldered for 10 months, lit by Lemieux in Game 6 of the 1996 Western Conference finals, when he rammed Draper from behind face-first into the boards near the Detroit bench, breaking his jaw, cheekbone, orbital bone and nose, displacing teeth, causing cuts around his right eye, and leaving him concussed.

“I was sitting on the bench, and it happened right in front of me,” McCarty said two decades later. “It was like seeing a car crash in slow motion. I could literally hear the bones break in Drapes’ face. It was difficult for us to process.”

Trainer John Wharton summed up the carnage: “I’d be hard pressed to find and add together three or four head and facial injuries that would accumulate to the damage that this one injury has caused.”

Despite receiving a game misconduct, and eventually a suspension, Lemieux claimed the hit was “shoulder to shoulder … it wasn’t a clear hit from behind.” He suggested it was Draper’s fault. “He turned to the bench right when I hit and that’s why he was injured.”

Adding insult to injury, Lemieux watched and then celebrated as the Avalanche eliminated the Wings after their 62-victory regular season. “He’s a goonish hockey player,” Draper said the next day. “He not only had no remorse about the hit, he embarrassed the Wings by the way he was talking about our performance the past few years. He has no class whatsoever.”

It wasn’t even the only hit of the series that earned Lemieux a suspension; he had been penalized one game after sucker punching Slava Kozlov in Game 3. He received just a two-game suspension for the hit on Draper. He never apologized. Draper seethed.

“Is the league telling me I have to take things into my own hands?” Draper said a few days later. “Do I have free rein on Claude Lemieux next year? The league didn’t even come close to taking care of it.”

In 2017, marking the 20th anniversary of Fight Night at The Joe — as March 26 would come to be remembered — McCarty discussed an unspoken pact among the Wings.

“The only thing that was ever said between any of us in the room,” McCarty said, “was between me and Drapes 10 months earlier in May, two days after he got his jaw wired shut and his orbital bone broke. I said two things. I said, ‘Don’t worry. I’ll take care of it.’

“That’s the only thing I ever said. Then I asked him where he wanted to eat, but I knew it was Andiamo.”

Lemieux was sidelined by abdominal surgery in November 1996, when the Avalanche made its first visit of the next season to The Joe, and in December when the Wings traveled to Denver. Draper and Lemieux — plus McCarty — were in the lineup for the season’s third meeting, March 16, 1997, at Denver’s McNichols Arena.

With 22 seconds left in the first period, Draper and Lemieux came together during a Joe Kocur-Sandis Ozolinsh skirmish. Draper and Lemieux, after being separated, mouthed off and received 10-minute misconducts.

“Kris and I had a bump in that game, and I asked him if he wanted to settle it then,” Lemieux said two decades later, “but nothing happened. I thought that just maybe people had moved on.”

Hardly. Ten days later at Joe Louis Arena, McCarty remembered his 10-month-old vow. “I always planned,” he said, “on doing it in front of our fans at home.” Plus, the Wings had lost all three meetings with the Avs — by a combined score of 12-6. Their last victory against their heated rivals had been in Game 5 of the conference finals.

“When we came to Detroit for the March 26 game,” Lemieux recalled, “the NHL security had a guard outside my hotel room. Before the game, the league suggested we wear helmets during the warm-up, because they were afraid of stuff being thrown at us. I was more worried about being hit with a beer bottle than I was about what was going to happen on the ice.”

McCarty said in a 2017 interview with the Free Press: “Claude was going to get gonged one way or the other.”

VOICE OF THE TURTLE

McCarty held him by the back of the neck with one hand and swung repeatedly with the other, throwing punches that seemed to have the force of the entire, roaring building behind them.

— Mitch Albom

When Lemieux skated onto the Joe Louis Arena ice March 26, it was to the sound of deafening boos. No bottles were thrown, though.

There would be 10 fights in all, although officials for unknown reasons did not consider McCarty’s one of them.

Jamie Pushor and Brent Sevryn tangled 4:45 into the first period, although neither landed a punch. Pushor got off seven punches but was wrestled to the ice first. Five minutes passed. Kirk Maltby and Rene Corbet were waylaid by officials before any real punches connected. Maltby landed on top.

Then, a firestorm started with two of the least likely combatants: Igor Larionov and Peter Forsberg, men of European descent more comfortable letting their handiwork show with exquisite passes, not punches. With 100 seconds left in the first period, after Larionov dropped a pass near the blue line for McCarty, Forsberg shoved Larionov, who fell backward against the boards and to the ice. As Larionov started to rise, Forsberg delivered a short elbow to the side of his head.

“I simply had enough,” Larionov said two decades later. “You can only take so much.”

In his book “The Russian Five,” longtime Free Press hockey writer Keith Gave described what Larionov did next this way: “Larionov turned and, with his glove still on his left hand, he landed the first and only punch he had ever thrown in his Hall of Fame career. He didn’t back off, either, putting Forsberg in a headlock.”

Larionov wrestled Forsberg to the ice. They would receive only roughing penalties for their uncharacteristic roughhousing. But they unleashed the gates of hell. Ten minutes of all-out brawling ensued as the crowd went insane.

“Never in my life did I have any fights, and I’m not proud about that situation,” Larionov told Gave for his book. “But there are certain times when you must stand up for yourself.”

Referee Paul Devorski and his two linesmen rushed to untangle Larionov and Forsberg as other players raced to the scene. At some point, Forsberg was cut by a skate. McCarty, though, slipped out of the vicinity. He headed in the opposite direction hunting for Lemieux.

Colorado’s Adam Foote and a linesman found McCarty first. Each had a piece of his jersey. That’s when Brendan Shanahan ensured — for the first time — that McCarty could abuse Lemieux.

“He knew that I wanted Lemieux,” McCarty said in 2017, “so he chopped at Foote, which sent me loose.”

McCarty, at 6-feet-1, 215 pounds, spun away and quickly reached Lemieux, also listed at 6-1, 215. Lemieux, despite his well-earned reputation as an on-ice agitator and a cheap-shot artist who could score goals and contribute assists, rarely dropped his gloves to fight.

In a 21-year career starting in 1983 that spanned 1,215 games and three Stanley Cups, Lemieux fought only 36 times, according to hockeyfights.com, and 21 of his bouts came in his first seven seasons. McCarty, meanwhile, had 23 fights just in his rookie season, 1993-94. He finished with 136 fights in a 15-year career that covered 758 games and included four Stanley Cups.

At The Joe on March 26, 1997, Lemieux stood alone, still holding his stick, apparently watching Larionov and Forsberg scuffle from a safe distance.

“When I saw that, I thought, ‘Uh-oh, this is not good,’” Lemieux said two decades later. “I probably should have had my gloves off. I didn’t want one of those crazy brawls. I just wanted the game to be over with.”

On the replays, he seemed oblivious to the mayhem. He never noticed McCarty headed his way. He also never saw the first punch.

McCarty coldcocked him with a right-gloved haymaker to the right side of his head. Lemieux fell hard on his back. He then rolled to his right and onto all fours, as McCarty pounded him with lefts. Lemieux started to get up while throwing off his left glove, but it was too late. McCarty threw a vicious left to his face, and Lemieux collapsed into a head-ducked turtle position.

It was a heavyweight versus a deadweight.

That’s when Shanahan ensured — for the second time — that McCarty could abuse Lemieux.

Intent on entering the fray, goalie Patrick Roy made a mad dash to center ice. He never made it, intercepted by a leaping bear hug from Shanahan instead.

“There was a little WWF from both of us there,” Shanahan said. “I saw Patrick going for McCarty, and I didn’t want him to sneak up on him, so I went after him. When I was three feet in the air, I was thinking, ‘What am I doing?’ When I was five feet in the air, I said, ‘What am I really doing here?’”

Foote grabbed Shanahan. Goalie Mike Vernon, who raced from his crease after Roy left his, pulled at Foote. Shanahan and Vernon each ended up with one of Foote’s arms and spun him around until he hit the ice. Then Roy grabbed Vernon for a rare goalie vs. goalie slugfest.

McCarty dragged Lemieux about 10 feet and dumped him against the boards at the Detroit bench, right in front of Draper. Then McCarty kneed Lemieux in the head, drawing more blood, as two officials tried to pry him off Public Enemy No. 1 in Hockeytown. When the officials finally liberated Lemieux, he had blood pouring down his forehead and cheeks. He looked dazed and confused and exhausted.

“It brought everything full circle,” McCarty said in 2017. “It was, ‘Hey, Drapes, do you want to take a look?’”

After the game, Draper gushed: “Mac is such a team guy and he wanted to stick up for me. I consider us best friends, and I was happy he did what he did for me.”

The McCarty-Lemieux confrontation technically was not a fight, in the sense that Lemieux never threw one punch. It was an all-out beating. “Claude’s lucky he never got up,” McCarty said, “because it would have been a lot worse.”

Lemieux needed a linesman to help him to his feet and point him to the dressing room to get stitched up; he needed 10-15 to close a cut on the back of his head and a few more on his forehead. An official used his skates to try to disperse the blood that had pooled in front of Detroit’s bench.

Photos and videos of Lemieux turtling — with its implication that he acted cowardly — dogged him the rest of his career. Two decades later, in an interview with the Free Press, he had his explanation down pat.

“Darren hit me extremely hard on the temple, and the next thing I know, I’m down and getting hammered,” Lemieux said. “It happened so fast, like in a street fight. Everyone knows when you get dinged like that, you don’t know what’s happening, you’re dizzy. In a fight situation, you know when you’ve got the upper hand and when you’re getting your ass kicked. I knew it wasn’t going to be my day. I was not a coward. I wanted a rematch.”

To the surprise of everyone, McCarty received only a double roughing penalty and was allowed to stay in the game. Nearly a quarter-century later, Devorski explained his reasoning to Gave for his new book, “Vlad The Impaler: More Epic Tales from Detroit’s ’97 Stanley Cup Conquest:”

“My memory was … I just couldn’t forget what happened to Kris Draper. I’m getting ready for the game, and they’re showing the highlights on TV — Kris Draper’s face after he got hit. I’m thinking, ‘Holy (expletive).’

“I’m being honest with you: McCarty should have been thrown out. He should have got 2-5-10 and game (misconduct) and be gone. But my just gut told me, ‘This guy had it coming.’ I wouldn’t let it go. I couldn’t. So I told the linesmen, ‘No, I’m keeping him in the game.’”

Despite the beating Lemieux absorbed, in the tradition of hockey, he returned to the action — and nearly scored the game-winner.

“When he sucker punched me, I was hurt. I didn’t turtle,” Lemieux said in a 2010 Canadian television interview. “I never held a grudge against Darren because he stood up for his teammate. That’s what you should do in hockey.”

Lemieux still had a battle scar.

“When I have a haircut, I’ve been asked, ‘Where did you get that bump?’” Lemieux said. “Well, it’s from when Darren kneed me.”

The best fight of the evening was the most unexpected. Roy, at 6-2, 190, towered over Vernon, all of 5-9, 170. At center ice, they exchanged blow after blow. Vernon shed his blocker and glove; Roy kept using his glove to surround Vernon’s head. Each goalie landed four punches and one big one apiece. It ended with Vernon on top of Roy, two officials piled on top of them. Roy skated to his bench to wipe the blood off his face.

“I had a big smile on my face watching the goalies fighting and watching little Mike hold his own,” Maltby said. “I was surprised it went on for as long as it did, but the emotion was so high.”

“When you go through war,” McCarty said, “sometimes you need a little feistiness. To see Vernie in there slugging away, that’s great.”

Like McCarty, the goalies were allowed to stay in the game. In fact, despite the six-on-six melee, no game misconducts or even 10-minute misconducts were assessed. Only 22 minutes in penalties were handed out at the 18:22 mark: Roy and Vernon for seven apiece (leaving the crease and fighting), McCarty for four (double roughing) and Forsberg and Larionov two apiece (roughing). (The next day, McCarty called it “the best four-minute penalty I’ve ever taken.”)

Eleven of the 12 players on the ice arguably did something worthy of at least a five-minute or a 10-minute penalty. The exception? Lemieux, because the NHL had no rule against turtling.

A BATTLE ROYALE

You do what McCarty did in the NBA, the NFL or Major League Baseball, and you’re suspended immediately. In hockey? McCarty was back fighting by the second period. So was everyone else.

— Mitch Albom

Before the Wings and Avs could fight five times in the second period, 98 seconds remained to be played in the first. Fifteen seconds after the main event, Colorado’s Adam Deadmarsh crosschecked Vladimir Konstantinov and a fight, naturally, ensued.

Four seconds into the middle period, Shanahan and Foote tangled again. In their 45-second bout, they each threw 12 punches and landed five. It was scored a draw.

Then 3½ minutes later, simultaneous bouts pitted Aaron Ward against Severyn and Tomas Holmstrom against Mike Keane. The Ward-Severyn fight lasted 65 seconds, even though Ward never threw a punch. Severyn threw 10 and landed four. They “got so involved,” Albom wrote, “Severyn was stripped down to his waist, bare-chested, looking like some 1890s prizefighter.” Besides their fighting majors, Ward and Severyn received game misconducts — the only players so penalized all night.

Four minutes later, McCarty and Deadmarsh fought for 15 seconds, and Deadmarsh threw more punches (9-5), landed more punches (3-1) and connected on the lone big blow.

Another four minutes passed until the next — and final — on-ice fight. It matched Pushor against Uwe Krupp with 8:34 left in the second period.

At that point, the Avalanche led, 3-2, soon to be, 4-2. But as Steve Yzerman said: “For the first two periods, the issue of winning the game seemed to be completely irrelevant.”

Over the decades, hardly a voice in Detroit has questioned McCarty’s eye-for-eye frontier justice inflicted upon Lemieux. Maybe that’s because Lemieux was a notorious bully and cheap-shot specialist. Maybe that’s because the Wings won the fights, won the game and won the Stanley Cup. Fight Night at The Joe became an instant classic, and its legendary status only grew with each year.

At the time, however, not all corners approved of the on-ice violence. Teachers across the metro area felt compelled to address conflict resolution with students. The Free Press sought out experts to analyze the Big Picture; they recommended that parents hold similar conversations with their children.

From Steven Ceresnie, a Plymouth psychologist: “What happened taps into a very primitive part of human nature. We like to see car crashes, people falling off high wires, people getting knocked out in boxing. It doesn’t necessarily say anything horrible. That’s just the way human nature is. … It’s important to remember that with children, logic often flies out the window and emotions can take over. So parents have to present logic and reason.”

From Art Taylor, associate director of Northeastern University’s Center for the Study of Sport in Society: “The ‘it’s payback time’ atmosphere is very uncivilized. Claude Lemieux is a dirty player. You hate to see a bully get away with something. But to endorse violence, to encourage it, to not head it off plays to the worst part of ourselves. … It would have been better to put Lemieux in a dunk tank or something. … This isn’t the way we want to teach kids to settle things.”

Inside the Free Press’ newsroom, a significant number of high-ranking editors did not approve of the Sports section’s giant “Bloody good” headline or its photograph of a bloody goalie. The Sports staff thought these editors were overly sensitive, just plain wrong or batcrap crazy.

HOW THEY SCORED

Here was the great part of Wednesday night, when the game tilted back to sanity, when the punching stopped and the blood dried, it returned to being about skating and passing and honest checking and goaltending. And it was under the hot lights of those higher standards that the Wings battled back from a 5-3 deficit, tied the game … and pounded, pursued and pushed the Avalanche to the limit.

— Mitch Albom

Fight Night at The Joe unfolded as if two entirely separate events took place on the same evening. One was a mix of grace, speed and dexterity; the other was a display of pure brawn. By midway through the second period, the Wings had won the war of fists, avenging Lemieux’s cheap shot on Draper and fending off the Avs’ counteroffensives.

But, afterward, the Wings said to a man that as good as all that felt, it wouldn’t have meant as much if they hadn’t beaten Colorado for the first time since May 1996. To do that required no small feat.

In the first period, as the teams combined for 60 minutes in penalties and five fights, the Avalanche scored the lone goal. Valeri Kamensky one-timed a blur past Vernon’s right shoulder.

Sergei Fedorov, playing defense instead of forward, tied it 35 seconds into the second period. Fedorov, paired with Larry Murphy, whipped a wrist shot past Roy.

“I thought he was excellent,” coach Scotty Bowman said. “He played a terrific game offensively and defensively. We’ll see if we can continue the experiment.”

Kamensky beat Vernon again 1:12 into the period, and Martin Lapointe tied it again at 3:08. As the fighting subsided, the Avs took a 4-2 lead on goals by Corbet and Deadmarsh.

Most of the time, such a lead would have been insurmountable: Colorado entered the game 32-2-3 when leading after two periods. But what the Avalanche faced was an old-time team playing old-time hockey in front of fans seeking revenge of biblical proportions.

The Wings cut it to 4-3 when Nicklas Lidstrom spanked the puck from the left point past Roy with 19.1 seconds left in the second period.

They kept the pressure on Roy in the opening moments of the third period, sending pucks barely high and wide of the goal. At the other end, however, Kamensky completed a hat trick and appeared to doom the Wings 1:11 into the period.

But not on this high-octane night.

McCarty banged a shot from the top of the circle off the post. Then Lapointe buried a loose puck at 8:27, registering his first career two-goal game and cutting the deficit to 5-4. Only 36 seconds later, Shanahan used his soft hands for more than punching to tie it.

Stymied on three beautiful chances in the first period, Shanahan beat Roy by flipping the puck off the back of the goalie’s leg and into the net.

The action was fast and furious down the stretch. Lemieux nearly broke the tie with a hard, well-placed shot from just inside the blue line that Vernon barely deflected.

Overtime lasted 39 seconds. The right amount of time for a Hollywood ending. For the third time, Shanahan laid the groundwork for his linemate to claim the spotlight.

As the Avs pushed the puck up the ice, Shanahan rode Lemieux out of the play along the boards in the neutral zone. The puck skipped to Lidstrom just inside the Wings’ zone. He carried it to center ice and slipped a short pass to Larionov, who entered the zone, put a nifty move on Foote and slid a cross-ice pass to a wide-open Shanahan at the top of the circle.

McCarty, meanwhile, had been streaking down the left flank and was behind the Avs’ defense. Shanahan pushed a perfect pass across the ice, between two defenders and onto McCarty’s stick. Roy tried to slide across the crease, but McCarty one-timed the puck into the back of the net. The red light flashed, the crowd exploded and the Wings finally had defeated the Avalanche.

“I don’t think it could happen to a better guy,” Draper said.

BROTHERS IN ARMS

The honest reader will admit that what McCarty did to Lemieux was just as bad as what Lemieux did to Draper. But sports have rarely been about honesty and have always been about partiality. So you see Draper and McCarty and maybe, even despite yourself, you smile. … In one night, McCarty fought with the devils and heard the angels sing.

— Mitch Albom

The Avalanche coaches and players were incensed after the game. Coach Marc Crawford elbowed Ward, already dressed after his ejection, in the ribs in the hallway leading to the locker rooms. He tried to barge into the officials’ locker room. And he blasted the officiating in his postgame comments.

Keane, an alternative captain, declared, “That team has no heart.”

“Detroit had the opportunity to do that in our building, but they didn’t,” he said. “They come home and play it rough. That’s fine. I think they showed their true colors tonight. Everyone is gutless on that team, and I’d love to see them in the playoffs.”

Be careful what you wish for. …

Draper was asked point-blank: “So, do you consider this Lemieux issue settled?”

He paused. “Sure. I like closure. If that’s closure, then it’s perfect.”

Northeastern’s Taylor thought Draper’s comment was shortsighted.

“There’s always another side,” he said the next day. “The McCoys may have been saying that, but not the Hatfields. Only one side got to say that at a time.”

Fight Night at The Joe reverberated throughout the hockey world. Imagine if social media had existed. Instead, ESPN’s highlights, sport-talk radio and newspapers, many just dipping their toes in the Internet, carried the load.

Frank Orr of the Toronto Star wrote: “It was a match that should be an embarrassment to the NHL except for one small fact: The league’s skin is thicker than any elephant’s.”

Dave Fuller of the Toronto Sun wrote: “The Motor City may not have seen this much violence since Jimmy Hoffa headed up the Teamsters union.”

Bob Kravitz of the Rocky Mountain News wrote: “There will be no tears today for Claude Lemieux. Because he got what he deserved. It wasn’t one of Lemieux’s better moments, and it revealed why Lemieux, and players of his ilk, are so reviled by opponents. Because they are willing to give cheap shots and yap and make trouble but are unwilling to take off the visor and go toe-to-toe in a fight. In a world that is governed by hockey’s laws of the jungle, Lemieux is an unwelcome anarchist who rarely is willing to trade punches.”

The day after, Crawford singled out Devorski. “I thought the referee did as poor a job as he possibly could under the circumstances,” he told a Denver radio station. He also predicted the NHL would suspend McCarty and for longer than a wrist slap.

Nine Wings were given the day off to recuperate from the battle royale. McCarty defended his actions. Draper said he was glad Lemieux wasn’t seriously hurt and could continue playing.

Draper said: “I don’t want anyone to go through what I went through.”

McCarty said: “Altercations like that happen all the time and they’re within the rules, I thought. I didn’t hit him from behind. I didn’t take a cheap shot with the stick. I used my fists, and fists are a part of the game.

“What are you going to get, a few stitches, a black eye? Rather than going around wielding a stick and knocking guys’ eyes out. …

“It’s a high-emotion game out there and things happen. I don’t regret what I did. It’s part of the game.”

Two days after Fight Night at The Joe, the Wings were back in action along the Detroit River. Word came down a few hours earlier from Brian Burke, the NHL’s director of hockey operations, that there would be no suspensions or fines. McCarty celebrated with a victory lap before the game.

He hung around after every Buffalo Sabre and Red Wing had cleared the ice. He shot pucks into an empty net as the fans roared. Then, as the Zambonis went to work, he began throwing pucks to fans along the boards.

No athlete was more popular in Detroit.

Right after the game, the day after, throughout the playoffs and across the decades, the Red Wings never downplayed the importance of avenging the Draper hit and beating the Avalanche. Those two acts drew the players closer, renewed their confidence and strengthened their resolve.

That night, Vernon said: “This was a game that brought the Wings together. We can really build on this win as a team.”

The next day, associate coach Dave Lewis said: “The way you’d like to feel about it is, if you take your left and right hands, they’re still two hands, but now they’re together. The team is truly a team.”

Years later, Shanahan said: “Winning that game was even more important than winning the fights. I don’t know if that game brings our team together as much if we don’t also get the victory.”

Years later, Larionov said: “Every guy did their job to help the team win that game, and it kind of turned things around mentally and physically for us. It gave us the proof we can beat anybody.”

And also years later, broadcaster Mickey Redmond, the Wings’ first 50-goal scorer in the 1970s, said: “Up until that night, the team was a bit like being out in the ocean without a compass. That game bonded the team, gave them confidence and brought a closeness that nothing else could have done. It jump-started the Wings right to the Stanley Cup parade and helped propel one of the greatest rivalries in sports for several years.”

And, in a 2017 article for the Players’ Tribune, Draper wrote: “The brawl was one thing. But us winning that night changed everything. It gave us the belief that we could beat them in the playoffs. We knew we’d see them again in the Western Conference finals. We just knew. When they dropped the puck in that series, the tone had already been set. The vibe was different. As soon as Lemieux turtled at The Joe, everything changed.”

Despite all the bad blood — and actual blood — during Fight Night at The Joe, the events on the ice actually ended with a quiet bit of sportsmanship.

After McCarty’s overtime goal, the Wings rushed the ice to celebrate the dramatic finish as if it were Game 7 in the playoffs. The crowd noise all but lifted the roof off an arena once derisively called a warehouse on the waterfront.

Amidst the Detroit euphoria on the ice and in the stands, Roy fished the puck out of his net and shot it down to Vernon as a memento of his 300th victory.

They weren’t friends. They had been bitter rivals since their rookie season, 1985-86, when Roy’s Canadiens beat Vernon’s Flames in the Stanley Cup Finals. They had traded venom at center ice that night.

“I wasn’t surprised he did it,” Vernon said. “We respect each other. … He showed class. Patrick’s not a bad person. Some guys might not have done it.”

Old-time hockey.

Excerpted from “Stanleytown 25 Years Later: The Inside Story of How the Stanley Cup Returned to the Motor City after 41 Frustrating Seasons” by the Detroit Free Press.

ABOUT THE BOOK

Red Wings fans will never forget Steve Yzerman, with his gap-toothed smile, hoisting the Stanley Cup on the final night of the 1996-97 season. Or the Russian Five. Or the Grind Line. Or Fight Night at The Joe against Claude Lemieux, Patrick Roy and the hated Avalanche. Or the flying octopi. Or the one million fans who lined Woodward for the parade.

To commemorate the 25th anniversary of one of Michigan’s most-beloved teams, the Free Press crafted a 208-page, full-color, hardcover collector’s book with fresh insights and dynamic storytelling about the 1996-97 Wings.

THE FIGHT CARD

The epic game between the Red Wings and Avalanche on March 26, 1997, at Joe Louis Arena featured 39 penalties, 148 penalty minutes and 10 fights. Dropyourgloves.com — a website devoted to hockey fights, naturally — scored the bouts 3-2-5 in Colorado’s favor. But the Wings won the main event — Darren McCarty vs. Claude Lemieux — and the top undercard fight — Mike Vernon vs. Patrick Roy. A breakdown of the fisticuffs (Colorado pugilists listed first), according to dropyourgloves.com, a defunct website:

BRENT SEVERYN VS. JAMIE PUSHOR

When: 4:45 into the first period.

Duration: 20 seconds.

Size: 6-feet-2, 211 pounds for Severyn; 6-3, 218 for Pushor.

Punches by Severyn: One thrown, none landed.

Punches by Pushor: Seven thrown, none landed.

Blood: None.

Winner: Draw.

RENE CORBET VS. KIRK MALTBY

When: 10:14 into the first period.

Duration: Four seconds.

Size: 6-0, 195 for Corbet; 6-0, 195 for Maltby.

Punches by Corbet: One thrown, none landed.

Punches by Maltby: None.

Blood: None.

Winner: Draw.

CLAUDE LEMIEUX VS. DARREN MCCARTY

When: 18:22 into the first period.

Duration: 21 seconds.

Size: 6-1, 215 for Lemieux; 6-1, 215 for McCarty.

Punches by Lemieux: None.

Punches by McCarty: Eight thrown, eight landed (all big ones).

Blood: A lot from Lemieux.

Winner: McCarty.

PATRICK ROY VS. MIKE VERNON

When: 18:22 into the first period.

Duration: 22 seconds.

Size: 6-2, 190 for Roy; 5-9, 170 for Vernon.

Punches by Roy: Six thrown, four landed (one big one).

Punches by Vernon: Five thrown, four landed (one big one).

Blood: A lot from Roy.

Winner: Vernon.

ADAM DEADMARSH VS. VLADIMIR KONSTANTINOV

When: 18:37 into the first period.

Duration: 15 seconds.

Size: 6-0, 205 for Deadmarsh; 5-11, 190 for Konstantinov.

Punches by Deadmarsh: Five thrown, three landed (one big one).

Punches by Konstantinov: One thrown, none landed.

Blood: None.

Winner: Deadmarsh.

ADAM FOOTE VS. BRENDAN SHANAHAN

When: Four seconds into the second period.

Duration: 45 seconds.

Size: 6-2, 220 for Foote; 6-3, 220 for Shanahan.

Punches by Foote: 12 thrown, five landed.

Punches by Shanahan: 12 thrown, five landed.

Blood: A bit.

Winner: Draw.

MIKE KEANE VS. TOMAS HOLMSTROM

When: 3:34 into the second period.

Duration: 18 seconds.

Size: 5-10, 185 for Keane; 6-0, 198 for Holmstrom.

Punches by Keane: Three thrown, two landed.

Punches by Holmstrom: Three thrown, two landed.

Blood: A bit.

Winner: Draw.

BRENT SEVERYN VS. AARON WARD

When: 3:34 into the second period.

Duration: One minute, five seconds.

Size: 6-2, 211 for Severyn; 6-2, 209 for Ward.

Punches by Severyn: Ten thrown, four landed.

Punches by Ward: None.

Blood: None.

Winner: Severyn.

ADAM DEADMARSH VS. DARREN MCCARTY

When: 7:24 into the second period.

Duration: 15 seconds.

Size: 6-0, 205 for Deadmarsh; 6-1, 215 for McCarty.

Punches by Deadmarsh: Nine thrown, three landed (one big one).

Punches by McCarty: Five thrown, one landed.

Blood: A bit.

Winner: Deadmarsh.

UWE KRUPP VS. JAMIE PUSHOR

When: 11:26 into the second period.

Duration: 27 seconds.

Size: 6-6, 235 for Krupp; 6-3, 218 for Pushor.

Punches by Krupp: Nine thrown, four landed.

Punches by Pushor: Eight thrown, four landed.

Blood: None.

Winner: Draw.

Compiled by Bill Dow.

This article originally appeared on Detroit Free Press: Inside Detroit Red Wings-Colorado Avalanche 1997 epic brawl