Embryo development discovery could help prevent early miscarriages

The vital first days of a human embryo's life have been studied in new detail that could help understand and prevent early miscarriages.

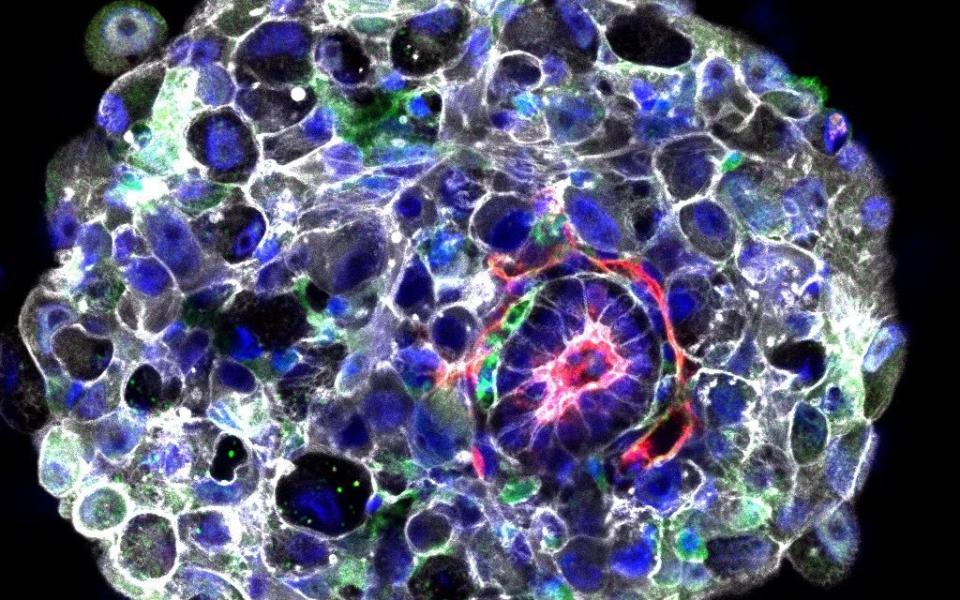

Researchers from the University of Cambridge studied embryos in their first two weeks of existence, focusing on how they transform from a clump of cells into an organised mass. This step is crucial in allowing a baby to develop, and the pregnancy will fail if it does not function perfectly.

Scientists hope learning more about this process will enable them to understand why many pregnancies end in miscarriages within a fortnight of conception.

Each birth – of which there are more than 2,000 a day in the UK – is the cumulation of an untold number of interdependent biological, chemical and physiological processes. Unpicking and mapping the nine-month incubation has long been a goal of scientists but, despite huge progress, some intricate details remain unknown.

One such mystery was the formation of the "head to tail" axis, which occurs at the end of the first week of an embryo's existence. It is the first time the symmetrical group of cells develops a layout.

This axis is critical for the foetal development of all mammals and is an invisible line which runs from the top to the bottom of an animal. It forms the basis of the gastrointestinal tract and determines the later growth and organisation of all the body's organs.

Researchers at the University of Cambridge studied the development of human embryos in a lab. Legally, embryos can only be used in research until 14 days post-fertilisation, at which point they must be destroyed on ethical grounds.

Embryos latch on to the womb wall around seven days after a sperm fertilises an egg, and this can also be replicated on a laboratory workbench.

The scientists found that the ambiguous embryo receives a chemical signal from a different group of cells known as a hypoblast around a week after fertilisation. These signals trigger a cascade of genetic modifications in the embryo that allows specific cells to begin specialising.

Hypoblasts were previously known to be involved in the development of the baby – but precisely how they did this was unknown.

Working with scientists at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the Cambridge team focused on the molecular conversations between the hypoblast and the embryo. They found that chemicals sent to the embryo from the hypoblast activate and inactivate various genes.

Before this happens, every cell of the embryo is pluripotent and able to become any cell in the human body, ranging from a bone cell to a neuron.

The hypoblast messages narrow the scope of each cell, creating the "head" and the "tail". Ultimately, this is the first step in ensuring the right organs and tissues are made at the right location. Without it, a pregnancy is not viable.

"We were looking for the gene conversation that will allow the head to start developing in the embryo, and found that it was initiated by cells in the hypoblast – a disc of cells outside the embryo," said Prof Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, the senior author of the study.

"They send the message to adjoining embryo cells, which respond by saying 'OK, now we'll set ourselves aside to develop into the head end'.

"Our goal has always been to enable insights to very early human embryo development in a dish, to understand how our lives start. By combining our new technology with advanced sequencing methods, we have delved deeper into the key changes that take place at this incredible stage of human development, when so many pregnancies unfortunately fail."

The full findings are published in the journal Nature Communications.