It was the ‘deadliest place’ for Black people in the US. That didn’t stop these high school students from changing history

USA TODAY’s “Seven Days of 1961” explores how sustained acts of resistance can bring about sweeping change. Throughout 1961, activists risked their lives to fight for voting rights and the integration of schools, businesses, public transit and libraries. Decades later, their work continues to shape debates over voting access, police brutality and equal rights for all.

MCCOMB, Miss. – Brenda Travis knelt to pray at the top of the steps outside McComb City Hall.

“Our Father,’’ she began.

Deputies, armed with billy clubs, stood guard at the entrance. Dozens of Travis’ classmates from Burglund High School crowded the sidewalk across the street, watching, waiting, holding signs. Some read “Freedom Now.’’

Before Travis could recite the Lord’s Prayer, two deputies yanked the 16-year-old student up, lifting her out of her shoes. They led her barefoot down a narrow dark staircase and into a jail cell in the basement of the building.

As she was led away, she heard a voice command: “Arrest all of these n-----s!”

Other students followed, crossing Broadway Street, climbing the nine steps, kneeling at the entrance of the brick building. They were arrested, too.

On Oct. 4, 1961, more than 100 students walked out of Burglund High School in McComb to protest Travis’ expulsion for participating in civil rights demonstrations. The students and others in the Black community were also angry about the brazen killing days before of civil rights activist Herbert Lee by a white state lawmaker. They wanted an end to racial violence, segregation and barriers to voting.

Their activism helped rally young people across Mississippi to challenge a system that blocked them from eating at whites-only lunch counters, waiting in whites-only sections of bus stations, attending whites-only schools and exercising the right to vote.

Many of the students went on to help organize other civil rights showdowns across the South, taking on leadership roles with pivotal organizations such as the Congress of Racial Equality, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the NAACP. In Mississippi, they helped launch Freedom Schools, where activists taught Black students, and Freedom Summer, where thousands, most of them college students, came to the state in 1964 to register Black people to vote.

“It was like a seed pod explosion and having seeds go all over the South and start sprouting,’’ said Bob Zellner, a former field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

Mississippi was a brutal training ground known for its fierce resistance to integration and its unchecked violence against Black people. Mississippi led the country in the number of lynchings of African Americans between 1877 and 1950, according to the Equal Justice Initiative, which pushes to end mass incarceration.

In McComb, the Ku Klux Klan reigned terror, bombing Black churches, restaurants and homes.

“For Black people in the state to say, ‘If these people can organize in McComb, where this is perhaps the single deadliest place to do anything like this, if they've got the courage to do that, then perhaps we've got the courage to be able to stand up and do something in our own communities,” said Robert E. Luckett, a history professor at Jackson State University in Mississippi.

Downstairs in the city jail that October day in 1961, Travis worried her mother didn’t know she had been arrested. Weeks earlier, Travis had been jailed for standing up to white power.

She had no idea the price she would be forced to pay for doing it again.

‘We wanted to mess the system up’

The clerks stared at the three young Black people approaching the counter on the whites-only side of the Greyhound bus station.

Weeks before the high school walkout, Travis, Ike Lewis, also a student at Burglund High School, and Robert "Bobby" Talbert, a NAACP member, wanted to challenge the segregated transportation system.

With the few dollars civil rights leaders had given her, Travis asked for a ticket to Tennessee. Within minutes police arrived, dragged the the three out and took them to the city jail for trespassing.

Travis, a NAACP youth leader, had wanted to get involved with demonstrations.

She followed news from a radio station out of New Orleans about protests in Black communities in the South. She admired the Freedom Riders, hundreds of activists – Black and white – who came mostly by bus to Mississippi starting that spring to challenge segregation in interstate travel. Some stopped in McComb.

That August, activists Hollis Watkins and Curtis Hayes had been arrested for sitting at the whites-only counter at Woolworth’s in McComb.

As a 10-year-old, Travis had been scarred by the image in Jet magazine of the mutilated body of Emmett Till, a Black 14-year-old who was killed in 1955 by white men in Mississippi.

A few days after she saw the magazine cover, police dragged her 13-year-old brother out of the family’s house and didn’t say why. He returned home late that evening. He never told Travis what happened.

Talbert, 20, was also upset by the slow pace of change.

The year before he had moved with his family from Chicago to McComb, where they had roots. About 13,000 people lived in McComb, an old railroad town 80 miles south of Jackson, the state capital.

Talbert worked as a carhop at a drive-in restaurant serving white customers hamburgers and soda pop. Black diners could eat only at a table in the kitchen.

He also caddied for white golfers, including the police chief. Black and white golfers couldn’t play at the same time.

Talbert knew he would be arrested at the bus station. He, Travis and Lewis spent nearly 30 days in Pike County Jail.

“We wanted to mess the system up,” Talbert said.

‘It felt like strong arms embracing me’

Travis stormed out of the principal’s office after she was expelled for her involvement with civil rights protests. It was Travis’ first day back to Burglund High School since serving time in the county jail after the bus station demonstration.

Despite being an all-Black school, Burglund was overseen by a white superintendent.

Schoolmates in the hallway persuaded Travis to go with them to the gym, where students had gathered for the weekly assembly. News of Travis’ expulsion spread.

In the gym, 15-year-old Jacqueline Byrd Martin sensed something was happening. Her older brother, Jerome Byrd, was president of the senior class, and he and other upperclassmen wanted to take a stand.

There had been rumors about a walkout if Travis and Lewis were expelled. Few knew when or if it would happen.

Martin, whose parents worked blue-collar jobs, had spent weeks that summer with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee canvassing Black neighborhoods to register voters.

Students knew the limitations of a segregated society. There were a few Black teachers and preachers in McComb. There was one Black doctor.

“We were being told that we could become anything that we wanted to become,’’ Martin recalled. “So how are you going to become anything you want to become if things stay the way they are?’’

After the assembly, Martin left her books behind and walked out of Burglund High School along with Travis and more than 100 other students.

“I don’t know if any of us knew how far that was going to go,’’ Martin said.

Travis looked back to see a parade of students trailing her.

“It felt like strong arms embracing me,’’ she said.

The students turned left onto Elmwood Street, past the cemetery, past Nobles Brothers Cleaners, past South of the Border soul food cafe – Black businesses that housed, fed and hid activists.

Along the route, barbers stopped cutting, beauticians stopped pressing hair. They cheered: “Go ahead, y’all! March! March!’’

Students sang as they marched on gravel streets:

We shall overcome, we shall overcome someday. Oh, deep in my heart, I do believe, We shall overcome someday.

Travis stopped outside the Masonic Temple, above the Burglund Supermarket. Inside was the office of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the new civil rights organization that had sent workers to her hometown to help demand change.

‘You could be killed any minute’: Civil rights veterans share horrors of battling white supremacy

Americans stood up to racism in 1961 and changed history. This is their fight, in their words.

‘All hell broke loose’

The civil rights workers were in a fierce debate: Should they focus on registering Black Mississippians to vote? Or should they hold more demonstrations, including sit-ins?

Their meeting was interrupted by the sound of young voices singing.

Teenagers filed into the SNCC office, grabbing black markers and white posters to make signs. Poles for posters weren’t allowed for fear they could be used as weapons by them or against them.

A mimeograph machine sat against one wall. Folding chairs rested along another. There were copies of the Mississippi Constitution to help prepare Black citizens to register to vote.

The SNCC activists had heard rumblings about a possible walkout. They immediately started assigning tasks: Some would march, some would be lookouts, some would report to headquarters.

“We joined right on in with them and moved right on out,’’ said Reginald "Reggie" Robinson.

SNCC had turned its attention that summer to Mississippi, sending staffers like Robinson and Bob Moses to work with local NAACP leaders such as Amzie Moore and C.C. Bryant on voter registration.

On the day of the walkout, activists were still rattled over the killing of Lee, who helped with voter registration. On Sept. 25, state Rep. E.H. Hurst shot Lee outside a cotton gin. Hurst claimed self-defense and was acquitted by an all-white jury.

Moore urged SNCC activists not to retreat after the killing. The group of mostly college students, Black and white, had come from Baltimore, New York, Alabama and rural communities across Mississippi.

“If y'all leave town now, them boogers got you,’’ Robinson recalled Moore telling them. “You ain't gonna never be able to do another thing in the state.’’

By the time the signs were finished, a mob had started forming at City Hall, the students' next stop.

Zellner, who was hired by the SNCC to recruit students on white college campuses in the South, questioned to himself whether he should march. Colleagues warned that his presence as a white man could stoke more anger.

Zellner decided he couldn’t sit out the fight.

“We headed downtown and all hell broke loose,’’ he said.

‘The police are coming from everywhere’

Zellner held tight to the black rail along the steps of City Hall. He worried that if he was dragged into the street, the crowd armed with pipes, bricks, bats, chains and wrenches would kill him.

Attackers pounded him with their fists. One tried to gouge out his right eye.

Dozens seemed to come out of nowhere, surrounding protesters on the steps.

Moses and others rushed up the steps, putting themselves between Zellner and his attackers. Police swung billy clubs at the activists.

Across the street in a phone booth, Robinson called the civil rights committee's headquarters in Atlanta.

’’They're whipping the shit out of them, boss,’’ he reported. “I'm telling you and everybody's getting in there. The police are coming from everywhere whupping ass every kind of upside down!’’

Downstairs in the dimly lit basement in City Hall, protesters were packed into cells.

Travis thought of her ancestors, enslaved Africans packed into ships. She imagined them struggling like her schoolmates to suck in air.

“It was tight, tight, tight,” she said.

Inside the dingy cells, protesters stood for hours on concrete floors. Small windows let in limited light.

The young people again turned to song.

Ain't afraid of your jail because I want my freedom. I want my freedom.

“We convinced ourselves that we were not afraid,’’ Travis recalled.

Protesters were charged with breach of the peace. Older ones were also charged with delinquency of a minor.

Watkins, the Woolworth’s protester, was one of the older protesters at 20 years old. He had been in the SNCC office when the students stopped there. He joined them and was among the first to kneel.

Officers took him to a room with two windows and a chair, leaving him alone. Minutes later, two white men in plainclothes opened the door.

“N-----, get up! Let's go. We're going to have a hanging here this evening, and your Black ass is going to be first,’’ one man yelled.

Watkins saw a rope with a noose tied in one of their hands. He calculated how best to kill them. Throw them out the window.

He looked them in the eyes as they approached. Then, with the same suddenness as they had appeared, the men left.

Later that evening, police led Watkins through the white crowd cursing him outside City Hall to a police car. He didn’t know where they were taking him.

“This might be my last day of life,’’ he told himself.

They tried to eat at a whites-only lunch counter in 1961. They were sentenced to a chain gang.

Deborah Berry: I'm blessed to hear living Black history from our civil rights veterans

‘It was time to be bold’

Travis found herself in the same cell at the Pike County Jail she had left a few weeks earlier.

Police had taken Travis and older marchers, including Watkins, to the county jail.

To get through the long days and nights, activists sang and read notes from McComb teachers, who shared news about protests in Nashville and Birmingham. Other Black supporters sent food: cornbread, fried chicken, butter beans, okra.

Travis had been there only a night when police escorted her to a patrol car. They didn’t say where she was going. She thought it was to see a NAACP lawyer in Jackson.

They drove for hours through the Mississippi countryside before pulling into a campus with red brick buildings. Travis asked the receptionist where her attorney was.

“Attorney?’’ the woman replied. “Honey, your attorney isn't here. This is a reformatory school.”

Travis spent nearly seven months in the Oakley Training School, a juvenile correctional facility. It was weeks before her mother, a cook and a domestic, learned where she was and managed to get rides from Jackson to visit.

Upon her release, Travis was exiled from Mississippi and put in the care of a professor in Alabama who she later said abused her.

Despite being banned from Mississippi, Travis returned in 1964 to help with the Freedom Summer registration drive.

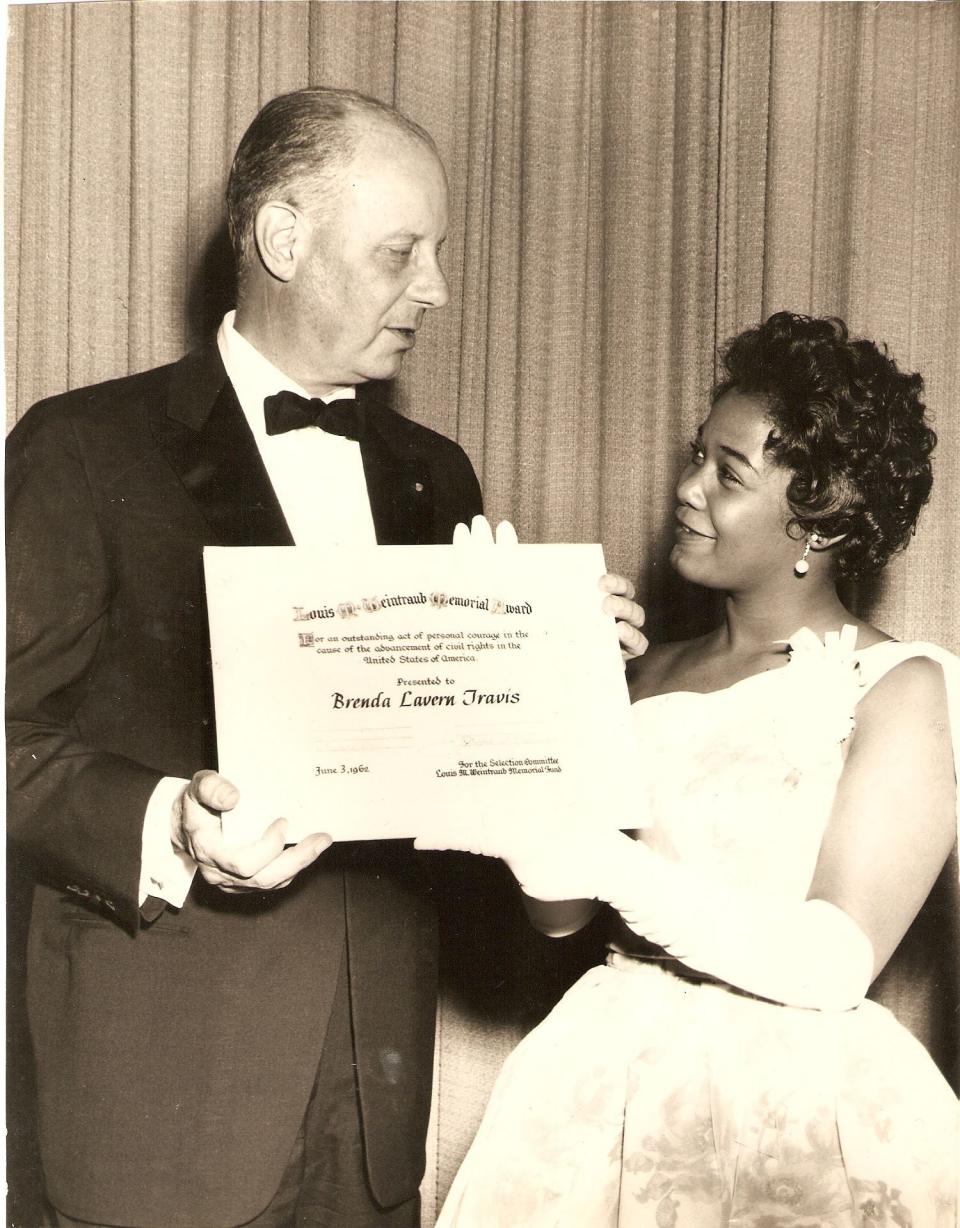

She continued her civil rights work in other states, co-wrote a memoir and in 2013 founded the Brenda Travis Historical Education Foundation to preserve civil rights history and encourage young people to fight for social justice. A street in McComb is named after her.

“It was bold to go down to the bus station. It was bold to walk the streets in protest. And it was bold for all of us to take the stand that we took,” Travis said. “But it was time to be bold.’’

Sixty years later, Travis and other activists worry their battles have lost ground. They point to dozens of states adopting measures making it harder to vote. And they complain that Congress has been slow to pass bills to better protect voting rights.

”It’s very disturbing to see us go back and fight fights that have already been fought,’’ said Travis, 76.

Other activists said they are also haunted by their work in McComb.

One recent afternoon, Talbert, now 80, returned to the jail below City Hall. It was his first time since his arrest there. He remembered it being much bigger.

He gripped the white bars and stepped into an empty cell. He sang “We Shall Overcome,” recalling a Freedom song he sang while in jail in the 1960s.

“One day I’m going to learn how to sing,’’ he laughed.

Talbert was arrested 62 times as a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee organizer. He has scars on his knee and elbow from iron pipes deputies used to beat him during a 1965 march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama.

The visit to the jail brought back memories of students and activists who dared to shake things up. “It was important then," he said. "It’s important now.”

To report these stories, USA TODAY interviewed veterans of the civil rights movement, historians and witnesses and reviewed public records.

Explore the series

Americans stood up to racism in 1961 and changed history. This is their fight, in their words.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Mississippi high school students protested injustice, made US history