A collection of Black history that asks you to take notice

It’s not a passive exhibit. As you enter the space at the Kitsap History Museum on Bremerton's Fourth Street, there is little written prompt to guide your experience. It’s the kind of exhibit where you have to dig in, maybe do your own research, sign up for a talk by the collector Roosevelt Smith or search our YouTube for past recordings. It’s an exhibit that requires viewers to do the work themselves. See the connections. Explore the history. Then dig into your emotional reaction.

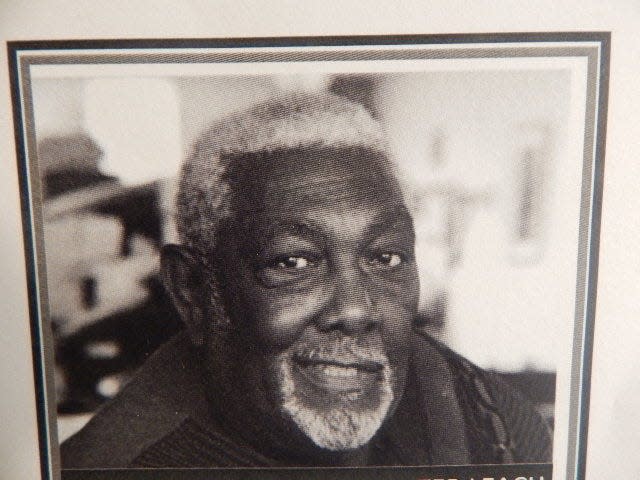

Roosevelt Smith’s exhibit, "State of the Union in Black and White," is more than a collection of Black Americana. It holds the history of the Black American experience. The good and the bad. The celebration of Black identity through Black Power art of the 196’s and '70s, the brutal history of enslavement and everything in between – chronicling the portrayal of Black people through media, objects and images.

Alone, one of these items happened upon in our day to day lives may go unnoticed. The stereotypes and caricatures of Black people permeate popular media to this day — our movies, our books, even our newsfeeds. But put these items together, hundreds of them organized on glass shelves, and it becomes gut wrenchingly apparent how egregiously Black Americans have been portrayed through the ages. For context, Smith’s collection includes some slavery-era items — a KKK application, slave rattles and ID tags, to name a few — to illustrate the beginning of the story. But many artifacts come from our not-so-distant past of the 1940s through '70s. My parent’s generation. More recent still, my life growing up in the '80s was filled with the Aunt Jemima Mammy and Uncle Tom archetypes. Smith’s collection forces you to take notice. It’s time we all stop looking away and instead, face the reality of how society continues to depict Black Americans. These images are so ingrained in the fabric of the American story and, consciously or no, absorbed by each and every one of us.

One of the stories that resonates with me is of the sanitation works of Memphis in 1968. I can hear Roosevelt Smith’s voice following up my use of the word “stories” here with a reminder that these are not fables or fictions, these are facts! Perhaps the more appropriate word would be “histories.”

Faced with low wage, unsafe, poor working conditions, the “Garage Men” of Memphis started organizing a union to lobby for better conditions. The City of Memphis refused to recognize the union and were determined to squash further organizing by firing the people rumored to be involved. The day the white supervisors summoned Baxter Richard Leach to their office started a revolution. Upon interrogation, the supervisor demanded “you boys” to go back to work and stop all this nonsense. To this, Leach replied. “I am a man! Not a boy!”

Speaking up to the white supervisors was a risky move and one that ultimately got him fired. Leach promptly joined his coworkers on the picket line. The months that followed were filled with threats from the city and harassments from White neighbors demanding the sanitation workers return to their routes to clean up the city. The strike lasted 14 months before the city ceded into recognizing the union. Baxter Richard Leach’s declaration became a mantra of the Civil Rights movement.

It’s hard for me as a white woman to understand the emotions that motivate building a social movement around the mere fact of my existence. I have never felt my life or my being challenged. Nor have I felt the need to declare it so. Baxter Richard Leach states “I AM A MAN!” He is not property. He is not ⅗ of a person. He is not an immature boy. He is a man. A man that deserves respect, same as any white man. A man that works long hours to provide for his family, same as any white man.

The “I AM A MAN” slogan resonates in my ears and rolls around my brain repeatedly, even after experiencing this exhibit on a weekly basis since last June. I think it’s because it feels so familiar. Nearly 50 years after Baxter Richard Leach Black Americans are still, to this day, campaigning for their very existence to be acknowledged.

Today the quest for racial equity sounds like “Black Lives Matter.” I am a man. I am a human being. My life matters. It matters as much as yours. Hear me. I exist. Same as you. See me. These are platforms of basic minimums.

If we truly believe that everyone’s lives matter equally, then we, as white people, should have no reserves saying loudly, proudly that Black Lives Matter. The needle towards justice won’t move until we can. Despite the black and white of the law writing us all as equals, the images we’ve absorbed throughout our lives influence our perceptions of Black people. Images like those found in this room, this exhibit. Racial equity won’t be achieved until we all dig into our shared history, uncover our societal bias, and challenge the status quo. Real justice comes from hearing Black stories, learning their lived experience and deeply believing their lives, do in fact, matter.

Thank you to the Black Americans pushing for social change. Baxter Richard Leach, Roosevelt Smith and so many others – your lives matter so very, very much.

Mary Phelps works part-time for the Kitsap History Museum, which displayed "State of the Union in Black and White: The Roosevelt Smith collection of Black Americana" this spring. The opinion expressed is her own, not on behalf of the organization.

This article originally appeared on Kitsap Sun: Opinion: A collection that asks you to take notice