Christine Sun Kim's vision rewarded with fellowship for disabled artists

You might recognize Christine Sun Kim from this year's Super Bowl.

The artist and California native soared to national recognition from the 40-yard line at Hard Rock Stadium in Miami, where she performed “America the Beautiful” and the national anthem in American Sign Language (ASL).

The moment was supposed to be a joyous one. Fox Sports, however, cut away from Kim to the football players — even though it had dedicated a “bonus feed” on its website to her performance.

A post shared by christine sun kim (@chrisunkim) on Feb 2, 2020 at 5:05pm PST

Her profile has risen even more since then. Kim has shown her work in MIT’s List Visual Arts Center, performed at the University of Toronto and unveiled a mural at Berlin’s biggest opera house.

On Wednesday, the artist achieved yet another distinction. Kim was awarded an inaugural Disability Futures fellowship, worth $50,000, alongside 19 other disabled artists, filmmakers, writers and creatives. The fellowship is the first multidisciplinary award of its kind and scale.

The Ford and Andrew W. Mellon foundations launched the initiative, which is administered by the arts funding organization United States Artists. The fellows were singled out as leaders in their respective fields: Rodney Evans in filmmaking, Jerron Herman in dance and Kim in visual arts, among others.

Kim, 40, hails from Orange County, Calif., but lives and works in Berlin. She uses performance, video, drawing, writing, technology and humor to reflect on her experiences as part of the Deaf community. (Like many others in her community, she prefers to capitalize "Deaf" to denote the group of people who share a language, like ASL, and a culture.)

The artist and activist first went to Berlin in 2008 for a brief art residency. It felt open, she said, and full of space. That space gave her room to breathe — both physically and mentally, stretching her ability to process.

The second time Kim went to Berlin, she met her now-husband, Thomas Mader, who's also an artist. (The pair recently participated in Berlin Art Week together, where Kim is part of the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum’s “Magical Soup” exhibition.) The third time she visited, Kim decided to stay. “Then we had a kid, and now here we are,” she said. “Yay!”

“But COVID's actually been the first time that I feel that I'm living in Germany,” Kim said through interpreter Beth Staehle in a Zoom interview with The Times earlier this week. “This is the first time where I feel like both feet are here, in Germany, rooted. I mean, it's different, but it feels good. It's new.”

Before the pandemic struck, Kim traveled. A lot. She used to go back and forth for work, often to the U.S., where her family is. Pre-shutdown, she went on a work trip to five cities: Miami, Boston, Denton, New York and Toronto. And she recently traveled to the Greek islands of Kos and the Kalymnos islands.

“What I've also discovered living abroad … is that I'm quite spoiled,” Kim said. “There's a lot of Deaf people that know American Sign Language.

“So it's like the same [way as] in spoken languages, where a lot of people know English, and you're like, 'But I wanted to practice this language in your country that I'm visiting you in.' But they want to practice their English with you, because you're an English-speaking visitor.”

A post shared by christine sun kim (@chrisunkim) on Jul 21, 2020 at 3:35pm PDT

Kim wouldn’t consider herself fluent in German Sign Language (DGS), but she knows enough to get by. Germany was also where she honed her sound art, which is essential to her work.

“That was also when I discovered sound as a medium for the first time,” Kim said, talking about her first trip to Berlin. “Because I know about sound, but I felt like actually considering it as my medium, as an artist, felt like a betrayal. It felt like I was betraying the Deaf community — but it was a false notion.”

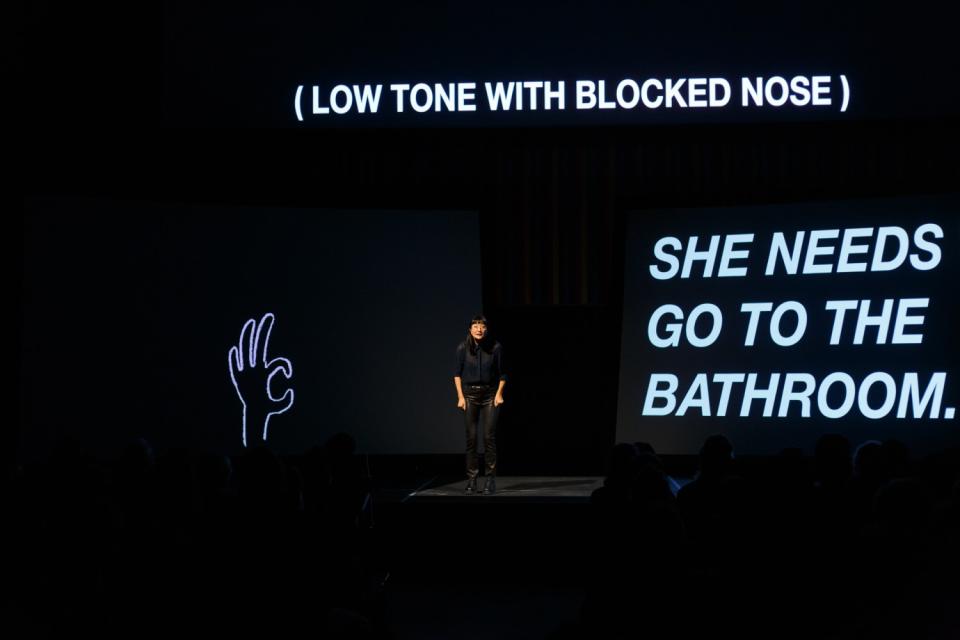

Now the artist uses the medium — alongside ASL, musical notation and televisual captioning — to comment on the social and political operations of sound. On Tuesday, Pop-Up Magazine posted a video story captured and captioned by Kim that turned the concept of closed captions on its head.

“She let us in on a not-so-well-kept secret: they suck,” the description read.

“I think the thing about captions is that they just lend themselves so well to poetry,” Kim said. “Because poetry is oftentimes that space between the language of nothing and a visual language like art to just straight-up content and language and information. So captions do the same thing.”

In the Pop-Up Magazine video, Kim tried her hand at writing her own closed captions for a largely silent video. Those included “[the sound of sun entering a bedroom]” over cloudy, blue skies, “[second wind]” with footage of a speckled turquoise coffee mug, and “[sweetness of orange sunlight]” over gently rippling waves.

“I would never consider myself a poet,” Kim said. “But I guess the thing is that I'm always in between a lot of languages anyways. I'm always in those spaces and places and missing bits of grammar or syntax or direct translations.”

A post shared by christine sun kim (@chrisunkim) on Oct 10, 2020 at 1:24pm PDT

More of her recent work includes a billboard in Hartford, Conn., created for the For Freedoms arts organization for civic engagement. The billboard is strategically located about 13 minutes away from the first Deaf school in the U.S., the American School for the Deaf.

Two years ago, For Freedoms began with the mission to erect 50 billboards, one in each state. Each billboard allows a different artist to ask the public a question surrounding the upcoming 2020 presidential election.

“So mine is: Why doubt my experience?” Kim said. “The reason why I chose that is because oftentimes, in regards to my Deaf identity, also being a woman, also being Asian American, I think sometimes I experience other people making decisions for me.”

A post shared by christine sun kim (@chrisunkim) on May 18, 2020 at 6:00am PDT

She’s not entirely sure what she’ll do with the Disability Futures fellowship money, but she knows it will let her keep creating work that amplifies minority communities.

“Money equals more time,” Kim said. “And the more time you have, the more you can sit and stew and meditate on your practice. You don't have to necessarily do.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.