Bad blood: Pro-Trump megadonors duke it out in Cornhusker country

Republican megadonor and Nebraska gubernatorial candidate Charles Herbster was there at the beginning of the Donald Trump era and the end — when the ex-president first came down the Trump Tower escalator to announce his campaign, and at the rally that preceded the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection.

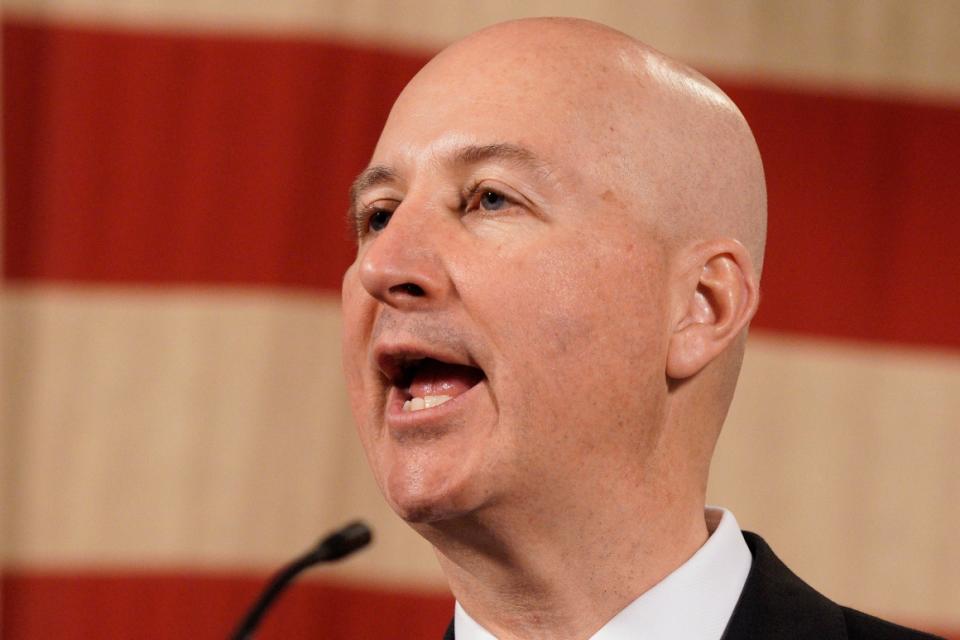

Herbster — who’s tapped former Trump lieutenants Kellyanne Conway and Corey Lewandowski to help run his campaign — could hardly have a more important friend as he tries to launch a political career in a deep-red state. But he’d also be hard-pressed to pick a more formidable adversary: current Republican Gov. Pete Ricketts, another wealthy, more recent Trump ally who’s determined to keep Herbster out of power.

Ricketts, who is term-limited and not running for reelection, has repeatedly accused the candidate’s agricultural company of shipping jobs out-of-state — a charge Herbster flatly denies. The governor’s team is promoting his attacks on Herbster through social media. And Ricketts’ longtime political adviser, Jessica Flanagain, has signed on with a Herbster primary opponent, millionaire hog farmer Jim Pillen, providing an early clue as to whom the governor may support.

It’s an unusual turn of events: Sitting governors rarely intervene in the campaigns to succeed them. But Ricketts — looking to maintain his home-state clout while simultaneously stoking speculation he could run for president in 2024 — isn’t giving Herbster an inch.

The clash illustrates a broader challenge confronting the roster of Trump associates seeking office in 2022, an increasingly long list that ranges from former ambassadors to ex-staffers to major donors. While their loyalty to Trump will almost certainly help them appeal to his die-hard supporters, they are also confronting the reality that their electoral fortunes could hinge on more local factors — in this case, a governor set on thwarting someone he views as an antagonist.

“It’s an open secret in the Nebraska GOP that Gov. Ricketts has no love lost with Charles W. Herbster,” said Ryan Horn, a Republican strategist in the state.

The fight could devolve into a financial arms race, pitting two powerful forces in Republican donor circles against each other. Herbster gave more than $1 million to outfits that backed Trump’s reelection effort, and Ricketts hails from a billionaire, Chicago Cubs-owning family that has lavished the GOP with massive sums. The 56-year-old governor has a long history of funding candidates in Nebraska he’s endorsed.

Who wins the battle could well be decided by their mutual ally: Trump, whose endorsement is certain to carry significant weight in a state he won by nearly 20 percentage points.

In an interview, Herbster insisted that he had no animosity toward Ricketts and said he was baffled by the governor’s decision to come out against him. He said he voted for Ricketts in both of his general elections, contributed to his first campaign and donated to his 2015 inaugural. Herbster recalled that shortly after taking office, Ricketts invited him to breakfast and asked for a contribution to a pro-death penalty initiative, which Herbster agreed to.

“I have nothing against Gov. Ricketts, I have nothing against the Ricketts family,” Herbster said.

But he added: “If I were governor of a state and I were the head of the Republican Party of that state, I would stay out of this race. I would focus on being governor. I would not focus on getting in the middle of … choosing who I would like to be governor.”

Ricketts did not respond to a request for an interview.

Nebraska Republicans trace the bad blood back to 2013, when Herbster gave millions of dollars to a Ricketts primary opponent, then-state Sen. Beau McCoy. McCoy savaged Ricketts, at one point calling him a hypocrite for opposing gay marriage while simultaneously being the co-owner of the Chicago Cubs, which McCoy described as a “gay-friendly” team. The attack was seen as deeply personal: Ricketts’ sister, Laura, is gay. (Herbster, who himself briefly ran before dropping out and endorsing McCoy, insisted he had nothing to do with McCoy’s criticism and didn’t agree with it.)

Compounding matters was Herbster’s then-alliance with outgoing Republican governor Dave Heineman, whom Herbster invited to serve on the board of his company. Shortly before the 2014 primary, Heineman endorsed Ricketts opponent Jon Bruning, whom Ricketts ultimately defeated narrowly for the GOP nomination. The Ricketts-Heineman feud would continue for years, with the Ricketts team later retaliating by releasing records depicting Heineman as engaging in extensive out-of-state travel during his time in office. (Heineman is now considering entering the 2022 governors race himself, according to multiple people familiar with his thinking.)

But Republicans in the state say there’s another reason why Ricketts may be so intent on stopping Herbster: Having someone he regards as a foe in the governor’s mansion, they contend, could become a headache in the event Ricketts chooses to mount a presidential bid. The governor has taken steps to cultivate a national profile in recent weeks, repeatedly attacking President Joe Biden on social media and appearing on a Fox News town hall event hosted by Laura Ingraham.

Ricketts began his assault on Herbster last week, holding a press conference the same day the candidate launched his campaign where he accused him of moving his company’s headquarters out-of-state — an assertion Ricketts repeated in a TV interview.

Herbster called the criticism “fake news,” insisting that he’s “never taken one job away from Nebraska.”

“I’ll be honest, I was very disappointed when he scheduled a [press conference] down the road from where I had my announcement,” Herbster said, “and took a cheap shot at me with a statement that was false.” (A Ricketts aide said the press conference had been planned well prior and described the timing as a coincidence.)

Herbster, 66, is known as a colorful figure within Nebraska circles: He owes his fortune in part to selling bull semen and talks about slapping Trump-themed license plates on his fleet of vehicles.

It is unclear whether Ricketts will try to use his influence with Trump to dissuade him from supporting Herbster. But Herbster — who said he hadn’t spoken with Trump about an endorsement — appeared to throw a brush-back pitch to the governor, noting that the governor’s parents donated millions of dollars to an anti-Trump super PAC during the 2016 Republican primary. Trump at the time issued a vague threat in response, tweeting that the Ricketts family has “a lot to hide!”

Herbster contrasted that with what he described as his steadfast support of the former president, whom he said he became friends with in 2005. He recalled being present at Trump’s 2015 campaign kickoff, spending the ensuing months flying across the country in support of his candidacy and becoming one of his first major financial backers.

Herbster, who spearheaded a Trump campaign agricultural advisory committee that year, said he rejected pleas to abandon Trump after the release of the lewd “Access Hollywood” video in which he spoke in sexually graphic terms about women.

Herbster’s loyalty has continued unabated. He attended the pro-Trump Jan. 6 rally that preceded the deadly assault on the Capitol, though he’s said he was not present for the riot and has condemned the violence that occurred. He was recently quoted in a local newspaper saying, “If it’s the difference between being disloyal to President Trump or becoming governor of Nebraska, I will not be disloyal to the 45th president.”

The Ricketts family, meanwhile, has come around to Trump. Just after Trump became the presumptive GOP nominee in 2016, he traveled to Omaha for a rally in which Pete Ricketts expressed his support.

During the 2020 election, the governor’s parents were among the former president’s most generous contributors, giving millions of dollars to pro-Trump organizations. Todd Ricketts, the governor’s brother, was nominated to serve as the Trump administration’s deputy commerce secretary before withdrawing. He was later named Republican National Committee finance chair.

But Herbster isn’t forgetting the Ricketts family’s initial opposition to the former president.

“I was loyal from day one, I can assure you,” Herbster said. “I spent two years in support of Donald Trump, when the Ricketts family was trying to do everything possible [to make sure] that he wouldn’t get elected.”