An ALF tragedy: COVID didn’t kill Rita at age 95, despair and loneliness did

Rita Thomas was a victim of COVID-19, but she never had the disease.

The vivacious and outgoing 95-year-old, who lived independently until last year and celebrated her most recent birthday in February with friends at a Pasco County diner, willed herself to die two weeks ago because she could no longer handle the pandemic-imposed isolation.

“She said to me: ‘Linda. I’ve had a good life. I am ready to die. I don’t want to live this way anymore. I stopped eating,’ ’’ her daughter Linda Gardner said, recalling the conversation she had with her mother in August. Weeks later, her mother was hospitalized for complications from malnutrition.

For the last 18 months Thomas lived at Rosecastle of Zephyrhills Assisted Living & Memory Care, an 85-bed long-term care community near Tampa. She filled her days with routine: dining out at restaurants, playing bingo and cards, going for daily walks and visiting every weekend with her daughter, family and friends.

But on March 13, when Gov. Ron DeSantis and the Agency for Health Care Administration ordered that visits be banned from nursing homes and assisted living facilities in an attempt to prevent the spread of COVID-19, all that daily activity stopped. Although the order allowed homes to make exceptions for certain family members to visit their relatives, most homes, including Rosecastle, resisted.

At first, Rita’s family accepted it. The coronavirus that was ravaging the globe preyed on seniors like Rita, who had recovered from a stroke and minor surgery but whose weakened immune system made her vulnerable to infection.

“Sometimes she’d say something like: ‘I just don’t understand. Why are they doing this to us?’ ” recalled Nan Thomas, Rita’s younger daughter. “We kept hoping they were going to open the doors and I would be able to bring her to my house again, and we’d go out to eat, get her strong.”

Instead, as the rest of the state opened up, the lockdown and isolation continued at Florida’s elder-care homes.

“I truly hold the governor and his medical advisers responsible for my mother’s quick decline and her pending death,’’ Thomas wrote to the Herald/Times, days after bringing her mother home to die rather than leaving her in a hospital.

“My mother didn’t die from a heart attack, or a stroke,’’ Thomas said this week. “She didn’t die from old age. My mother died from long-term isolation. That is what killed her.”

For his part, the governor has said a top priority is the safety and security of the state’s vulnerable elders.

Early in the pandemic, his emergency officials directed personal protective equipment and coronavirus testing kits to facilities. But he has also drawn criticism from advocates for his inconsistent and incomplete testing policy at long-term care facilities, waiting more than three months to require regular testing of staff, despite evidence they were the primary source of infection. And, starting this month, his Agency for Health Care Administration will no longer require staff at assisted living facilities like Rosecastle to be tested regularly for the contagious disease.

Perils of isolation

There is little data about the mental health effects of the extended lockdown at long-term care facilities in the United States, but medical experts have long known that prolonged isolation contributes to memory loss and other cognitive problems for older adults.

For Rita Thomas, the lockdown led to confusion and paranoia. She was allowed to walk outside, but she would forget how to get back in. She lost a hearing aid (which after her death her daughters would find in a cabinet in her room). She told her daughters that it was hard to understand the staff, who were wearing masks. She no longer remembered how to turn her TV on or off.

Instead of communal dining, the residents of Rosecastle were served three meals a day, alone in their rooms. She lost so much weight in six months that she went from a size medium to an extra small.

“All we knew is, she was miserable,’’ Nan Thomas said. “She could no longer go to her window to open the blinds and, in the last few months, she was too confused to know how to answer the phone for me to tell her to go to her window.”

There is emerging evidence that Rita Thomas is not alone.

“This isolation is becoming just as much of a pandemic in the facilities as COVID has,” said Brian Lee, director of Families for Better Care, an elder-care advocacy group. “But we’re not tracking it like we are COVID because that’s easier to track than isolation, despair, depression and suicidal ideations. That’s why it’s important we get the families back in to see what is going on.”

Rita Thomas’ death certificate read “failure to thrive,” her daughters said.

Dan Blazer, Duke University professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences is one of the authors of a report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine released in February that found that seniors who face social isolation experience a higher risk of mortality, heart disease, and depression.

Rita Thomas’ case “was extreme, but COVID exacerbates an issue that is already there for many older people,” he said.

“One of the major public health problems in our country is social isolation and [long-term care] homes want to keep COVID out of these institutions, so they lock down the institution. But, over a long period of time that is not good for older persons. It effects their health and their well-being.”

Should I go?

The staff at Rosecastle knew this, too. The home’s activities director, Marcee Riddle, said she tried her best to keep things normal for Rita and other residents. She organized parades, gathered small groups for exercises, held “Tattoo Tuesdays” with fake tattoos, and with the hairdresser not considered essential staff and no longer making appointments, Riddle tried to do her part to fill in.

“I put curlers in Rita’s hair,’’ she said Wednesday, choking up at remembering her friend.

Riddle also was so determined not to infect any of the residents, she completely changed her own lifestyle.

“I have not gone to a retail store since March 13,’’ she said. “My husband gets my gas for me; he goes to the store. I literally go from home to work and back, not only to keep myself safe, but to keep the residents safe.”

But for Rita, even the extraordinary efforts of some caring staff were no substitute for the touch of her loved ones. She began to be afraid to be alone in her own room, the one place where she was having to spend all her time.

She would walk the halls to escape her room, and at night would get anxious, so her daughters urged her to go to bed earlier each night. One night, she was so agitated Gardner had to sing her to sleep to calm her down.

There were glimpses of the kind-hearted mother they knew, whom they expected to live to be 100, like her relatives. Sometimes she would leave handwritten notes — about Riddle and other members of the staff whom she “just loves,” or simple kindnesses intended for Gardner and Thomas.

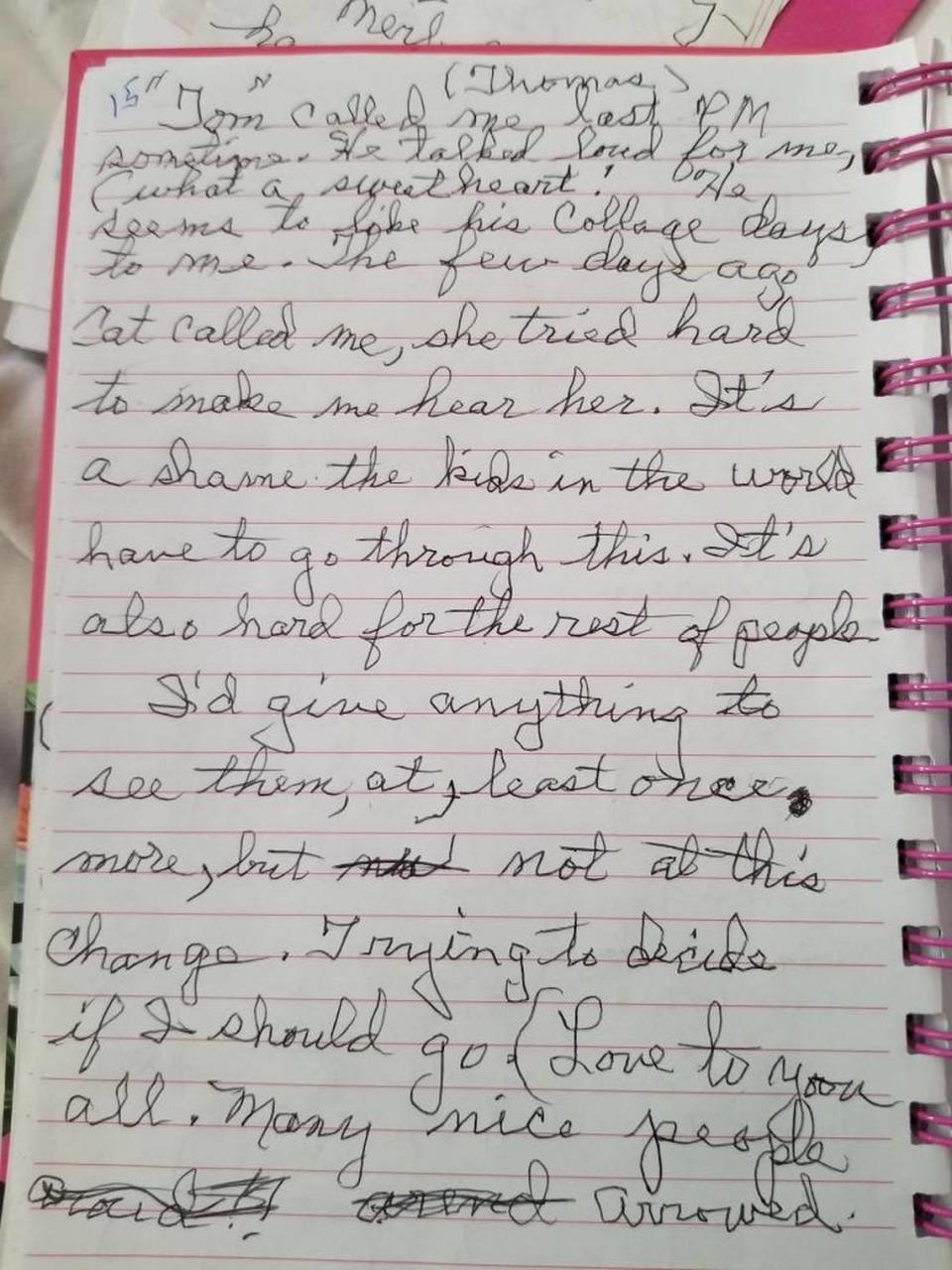

In classic penmanship, with a shaky hand, one haunting note mentioned a relative, then said: “I’d give anything to see them at least once more, but not at this change. Trying to decide if I should go. Love to you all. Many nice people around.”

Technology provided the sliver of regular contact they had. Gardner, who lives in Maine where Rita spent most of her life before moving to Florida in 1992, had set up an Echo Show device in her mother’s room. She used it to speak with Rita, who would often use it to call multiple times a day.

“The spark started to fade from my mother’s eyes,’’ Gardner said. “There was no spirit left.”

By August, the phone calls became further and further apart. ”She’d always ask ‘When is this going to end?’ ” Thomas recalled.

‘Cure worse than gamble’

But it didn’t end and, as Gardner worked on coaxing her mother through each day, Nan Thomas started writing emails to the governor, state Sen. Tom Lee, R-Thonotosassa, and her state Rep. Larry Maggard, R-Dade City, urging him to modify the rule.

“The cure is now worse than the gamble,’’ Thomas, who calls herself a conservative Republican, wrote June 17 to Maggard. “Each day her voice gets weaker. When she does answer her phone, she cries and asks me why I won’t visit her. I am losing my intelligent, spunky mother — not to coronavirus, but to the virus of politics and apathy.”

The only meaningful response came in an email from the Agency for Health Care Administration, days after her mother died, when they told her of the new visitation rule.

After pressure from families like the Thomases, the governor’s Task Force on the Safe and Limited Re-Opening of Long-Term Care Facilities convened in August to consider alternatives to the strict ban on family visitors. The governor signed a new order effective Sept. 1, allowing homes without a positive COVID case among staff or residents for two weeks to open the door to visitors under restrictions. But the rule is not mandatory, and the application of it remains uneven.

Because a Rosecastle staff member tested positive on Sept. 1, the rule barred it from accepting visitors until Sept. 15, and by then it was too late. Rita Thomas died on a hospital bed in her daughter’s living room on Sept. 18.

“When everything was taken from her — all normalcy, all routine and communication — the one place she had some power was her power to live,’’ Nan Thomas said.

Gardner, who has a background in long-term care and advocacy, told her mother she would support her when she chose to stop eating. But it was a painful place to be.

“I didn’t know how to help. I couldn’t help her,’’ she said. “I couldn’t even get on a plane. I mean, they didn’t want us traveling. You know, I ... I just felt so useless.”

Visiting mandates needed

Blazer, of Duke University, said there is a lesson here going forward.

“While the rest of the community opened up, they never really opened it up for for the elderly,’’ he said.

The use of technology, such as tablets and phones, as a substitute are “not ideal because many older people don’t have the skills or the equipment,” he said. He argues that, instead of “looking for quick, easy solutions,” regulators should “require homes to develop protocols that allow them to have visitors on a regular basis for people who live in their homes.”

Across the nation, Florida is among 43 states that have ended their ban on visitors in long-term care facilities and now allow some form of in-person contact, according to AARP. But few require homes to conduct visits, leading to vast variations within a state.

Steve Bahmer, CEO of LeadingAge, which represents 400 continuing care communities in Florida, said that all of their members are now allowing some visitors.

“In spite of our members’ constant efforts to use technology to keep residents connected to their families, there’s just no replacing being there in person,’’ he said. “We know that’s taken a toll in terms of loneliness and disconnection.”

Gardner and Thomas say they are grateful for the love and support of the Rosecastle staff, but are frustrated at what they consider a flawed and inconsistent state policy.

They describe how, after their mother died, they went to her apartment at Rosecastle four separate times to clean out her room, and only once were they asked to wear PPE. They wonder if a fear of lawsuits contributed to the lengthy ban on visitors, relaxed only when their loved ones are gone.

“You can’t sue anybody after that point,’’ Gardner said. “She was dead. They are protecting themselves.”

Chantel Aube, president of Rosecastle Management, which owns four facilities in Florida, didn’t address the liability issue but said the organization has “mirrored our policy and procedure based on the governor’s order.”

“It’s the inconsistency that has been frustrating,’’ Thomas said. “A delivery person can walk in my mother’s hallway, but I can’t. It’s the same virus everywhere but people are treated differently. It makes no sense.”

Mary Ellen Klas can be reached at meklas@miamiherald.com and @MaryEllenKlas