Taylor still on the mind of Redskins

When Santana Moss steps onto the Giants Stadium turf before Thursday's NFL season opener in East Rutherford, N.J., the Washington Redskins' eighth-year wideout will close his eyes and blurt out the initials of a pair of childhood friends who never made it to adulthood.

It's a ritual Moss has been performing before games and practices since arriving at the University of Miami as a freshman 11 years ago, and since last November it has been expanded to honor the memory of a third fallen comrade.

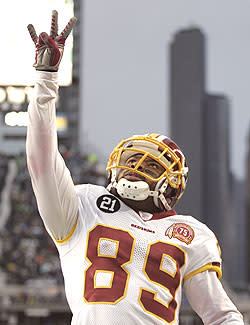

"Deuce to the one!" Moss will yell before beginning his pregame sprint. Then, he and many of his Redskins teammates will do their best to channel the ferocity and passion that slain safety Sean Taylor once brought to the field.

"That's me letting Sean know I'm still out here for him, thinking of him, remembering him," Moss said last month. "It hurts so much to think that he's gone. But for some of us, he'll always be part of this."

When Taylor, an ultra-talented fourth-year player seemingly headed for stardom, died last Nov. 27, a day after being shot by intruders during a robbery attempt at his Miami-area home, the impact on the Redskins transcended the loss of perhaps the franchise's best player.

Moss displays the "Deuce-One" after scoring a TD against the Seahawks in the playoffs.

(AP Photo/ John Froschauer)

For veterans like Moss and halfback Clinton Portis, the loss of their fellow UM alum and close friend was a brutal reality check – a reminder that life can be taken away at any time and should be afforded the requisite gravity.

For then-rookie safety LaRon Landry, the talented protégé whom Taylor had done his best to mold, it was an impetus to play with even more aggression and rage.

For virtually everyone on Washington's roster last fall, it was a jarring yet illuminating glimpse into how interconnected a football team can be – and how that normally unspoken chemistry can fuel an unlikely run of overachievement.

"When Sean died, each of us spent some time reflecting on how he had touched us – conversations we'd had, wisdom he had provided," Pro Bowl tight end Chris Cooley says. "Eventually, we all started piecing it together and realized, whoa, that was an amazing person. He'd impacted so many of us in so many different ways."

In the weeks after his death, it was tough not to believe that Taylor didn't have a profound posthumous effect on the Skins' surprising playoff drive. The emotionally devastated team paid tribute to Taylor in the first game after his death by lining up for the first defensive snap with only 10 men. Washington lost that game in excruciating fashion to the Buffalo Bills on a last-second field goal, then flew en masse to Miami for their former teammate's funeral.

With 36-year-old quarterback Todd Collins playing the rest of the way for injured Jason Campbell, the 'Skins proceeded to defeat the Bears, Giants, Vikings and Cowboys, the latter a 27-6 victory on the final day of the regular season to secure a playoff spot.

The next weekend in Seattle, things got even eerier. Washington rallied from a 13-0 deficit to take a 14-13 lead early in the fourth quarter on a 30-yard touchdown pass from Collins to Moss. The ensuing kickoff soared high above the Qwest Field turf before landing on the Seattle 14-yard line. Several Seahawks players were nearby, but none picked it up. The Skins' Anthony Mix recovered, bringing Qwest Field to a hush save the wild celebration on the visitors' sideline.

Some players pointed to the sky. They felt Taylor was still helping them.

The Seahawks felt it, too.

"If anybody had destiny on their side in the playoffs, it was the Washington Redskins," says new Washington coach Jim Zorn, who was Seattle's quarterbacks coach from 2001-07. "We had big fears of that."

The Redskins soon ran out of magic, losing 35-14 after a miserable flurry in the final minutes. Coach Joe Gibbs retired, and coordinators Al Saunders and Gregg Williams ultimately left. Zorn arrived with a different coaching approach, and the team's culture began to change.

Zorn understood, however, that Taylor would have to be a part of the new order. Early in training camp, Zorn told the team of his experiences in Seattle in 2003, when veteran passer Trent Dilfer's five-year-old son, Trevin, died after a sudden heart infection. "We would never, ever say to Trent, even today, 'You just need to move on,' " Zorn said to the players. "That's not something you get over. It's something you remember and that you have to live with every day, just as you guys will with Sean. Through you, his memory will live on."

The locker once occupied by Taylor at the team's Ashburn, Va., training facility remains as he left it, encased in Plexiglass. Zorn says there are plans to honor Taylor's memory at a game at FedEx Field early this season. Taylor's fiancée, Jackie Garcia, and their daughter, Jackie, visited the team's facility in mid-August. Executive vice president of football operations Vinny Cerrato still speaks semi-regularly with Taylor's father, Pedro, the police chief of Florida City.

"I think we'll always play for him," Portis says. "You look at this team and see we've got all these pieces in place, and you realize there's one person who's not here, but who should be."

Moss says Taylor's death had a deep impact on the way he views football and life. Over the offseason he married his longtime girlfriend, LaTosha Allen, with whom he has two children. He says he is more mature and more careful than he was before the tragedy struck.

"I can assure you it carries over for me, because it just let me know how easily this game can be taken away from you," Moss says. "Not only this game, but life. It's one of the greatest gut-checks I ever experienced. That man is gone.

"When he passed, that put another kind of surge in me, as far as what I needed to take care of as a man. When you're in this football world, it's almost like you're in college all over again – it's not like you're in the real world, with real responsibilities. Now I approach it differently. I've been ready to grow up for 13 years now."

Among other things, Moss says, "It just let me know that everybody's not my friend. Everybody that gives me hugs and daps me off and yells and screams 'You're the best!' isn't necessarily in my corner. When I talked to the authorities who investigated Sean's death and heard that the guys who robbed him were guys Sean knew, it blew me away. They knew him. They liked him. They knew his sister and loved his game and loved the guy that he was.

"But, you know, the economy sucks and these young kids don't want to work for anything, so they went to his house when they thought he wasn't home and figured, 'He won't know we did it.' Then he surprised them, and bam. Now somebody's life is gone – and their lives are basically gone, too."

(Last May one suspect accepted a plea deal and was sentenced to 29 years in prison; four others are expected to go to trial in March.)

Another player whom the tragedy hit especially hard was Landry, the sixth overall pick in the '07 draft. Almost as soon as NFL commissioner Roger Goodell called his name on the podium, Landry began hearing from people in NFL circles who cautioned him about Taylor's supposedly surly nature.

"Guys were telling me, 'He's going to be a hard guy to work with,' " Landry recalls. "But when I got here, it was the total opposite. He worked with me in meeting rooms and on the field and helped me get over that hurdle that all rookies face."

As the two safeties grew comfortable playing together, Cerrato began fantasizing about an extended run of greatness at the position. Taylor, the strong safety, "had phenomenal range and incredible ball skills. He was a kill-you-or-miss-you tackler." Landry, the free safety, "is a great blitzer and a great tackler who's still developing his downfield game. They were the perfect complement for one another – each guy's strengths complemented the other's weaknesses. And they'd have been playing together forever."

Taylor, left, talks to Landry during a preseason game last year.

(US Presswire/James Lang)

As part of his mentoring of Landry, Taylor used to give the rookie a ride to and from the team's training facility during the week. Upon learning of Taylor's death, Cerrato recalls, "LaRon starts crying and says, 'Who's gonna take me home?' "

It's a darker emotion that Landry has summoned since, at least on Sundays. Teammates noticed the way he stepped up his intensity after Taylor's death, intercepting a pair of passes in the playoff game in Seattle and looking for the type of big hits that No. 21 would have encouraged.

"Most definitely, I try to follow in his footsteps," Landry says. "I try to match his intensity, his style of play and bring what he brought to the team. I'll never be as great as he was. But all of this has inspired me to just … to just. … Well, instead of using the words I really want to use, I'll say to just go out there and lay it on the line."

What Landry was unwilling to say was something to which most men in his profession can relate: He plays angrier now, summoning more violence, looking to take out his pain on anyone in his midst. Before every game since high school, Landry has taken a pen and scrawled "Suicide Mission" on his chest. Those words have taken on added resonance since Taylor's death.

"It's not what you think," Landry says. "Obviously, this is not life and death. But it's a way of reminding myself that if I have to hurt my own body to do what I need to do, then that's what it's gonna be."

When Portis looks at Landry now, he sees "probably the next closest thing that you're going to find to Sean Taylor. He's next in line. Both are quiet guys. I could have an off-the-wall conversation with either one that leaves me shaking my head. And you never know what day they feel like talking. Some days you're chatting it up for hours, and some days you get the blankest stares and think, 'Man, that (conversation) never happened. What's going on in that dude's mind?' So you just sit back and wait for him to come to you."

One thing about Taylor's death that has bothered Portis and so many of his teammates is the way some journalists and others rushed after the shooting to assume that he had provoked the gunfire. Taylor, after all, had been the subject of a 2005 firearms-assault case, though charges were ultimately dropped as part of negotiated plea bargain.

Yet as Taylor's career progressed – and especially after his daughter was born in the spring of 2006 – he began to show a maturity that was noticeable inside the locker room. Taylor, however, remained distant and guarded with the media, and the negative public perception of him remained largely intact.

"What people didn't realize, but what we all knew, was that Sean had changed," Cooley says. "He was all about family. He really didn't go out. But he didn't show that side of himself to people on the outside, because he felt he'd been burned. It's too bad."

Taylor's teammates learned even more about him after his death when Garcia spoke to the team. Says Cerrato: "Jackie told them, 'You don't know how much you guys meant to Sean. Football was his life.' The guy had built a video room in his house and walked around saying, 'I've got to get better. I've got to improve.' And he had a huge heart. These guys will never forget."

Taylor remains a constant in Portis' mind.

(US Presswire/Mark J. Rebilas)

As they prepare for a new season, with a new coach and many new faces, the holdovers in the Redskins' organization look for any sign that Taylor is still with them. "We beat Dallas (last December) by 21," Cerrato says, shaking his head. "We lost to Seattle by 21 in the playoff game. And we had the 21st pick in the draft."

Deuce to the one. It's a number Moss will carry with him for the rest of his playing days.

"I look at the locker now and then," Moss says quietly. "I hope it's always there. Sean meant so much. I really think he was before his time."

Every night before he goes to bed, Portis updates his fallen teammate on the state of the Redskins, part of the "regular conversations I have with him, like he was still here." And sometimes, before he catches himself, Portis finds himself speaking as though Taylor's death never happened.

In August, while eating at a Mexican restaurant in Washington D.C., Portis struck up a conversation with a female diner and eventually told her what he did for a living.

The woman, who was a casual football fan, asked Portis, "Who's your favorite player?"

"Past or present?" he asked.

"Past."

"Bo Jackson. Or Barry Sanders."

"What about present?"

"My favorite player right now, hands down, is Sean Taylor," Portis said. The woman's eyes grew big, and there was an uncomfortable pause.

"To this day, that's my guy," Portis told her. "He's still here."