Should the Wonderlic test be used to evaluate NFL draft prospects?

The 50-question, 12-minute cognitive ability test has been used to evaluate NFL draft prospects for four decades now ... but does it work?

The Wonderlic test score results for NFL draftees aren’t supposed to be public, but somehow, year after year, they are. “We do not release test scores to anyone,” a Wonderlic employee told me, “except the NFL Combine representatives. Any Wonderlic test scores reported by the media are not official and could be inaccurate.”

Nonetheless, everyone pays a lot of attention to the Wonderlic score leaks this time of year, if only to argue about their merits. Just a few days ago, the sports press rushed to report that of this year’s crop, the three top running back prospects – Christian McCaffery, Leonard Fournette and Dalvin Cook – respectively scored 21, 11 and 11 of a possible 50. Immediately, speculation began on whether or not this would boost McCaffery’s stock when the first-round picks are called in the NFL draft on Thursday night.

Whether or not this means anything may never be known.

The test is made up of 50 multiple-choice questions to be answered in 12 minutes. The questions are designed to measure cognitive ability, which the website SharpBrains explains, “are brain-based skills we need to carry out any task from the simplest to the most complex. They have more to do with the mechanisms of how we learn, remember, problem-solve, and pay attention, rather than with any actual knowledge.”

Developed by psychologist Eldon F Wonderlic in the 1936, the aptitude tests are continuously updated and used in applications ranging from college entry tests to corporate team-building exercises. Chemists average a score of 31; electrical engineers, 30; teachers and reporters, 28; librarians, 27; secretaries, 24; electricians and nurses, 23. The test was brought to the NFL by Dallas Cowboys coach Tom Landry in the 1970s.

One of the first to write about the Wonderlic’s role in drafting players was veteran sportswriter Paul Zimmerman in The New Thinking Man’s Guide to Pro Football (1987). Interestingly, the average scores Zimmerman reported pretty much hold today.

Scores by football players vary greatly by position. The top five average scores by position, based on the unofficial results that have been reported through the years, are all on the offensive side of the ball. Keep in mind that a score of 20 is considered to represent average intelligence.

Offensive Tackle 26

Center 25

Quarterback 24

Guard 23

Tight end 22

Three of those five are from the offensive line. If you want to count tight end as part of the offensive line, and many coaches would, then make that four of the top five. The defensive positions rate considerably lower than tight end. The bottom two positions, rating well below the top five (and mark for “average” intelligence) are:

Wide receiver 17

Running Back 16

It’s tempting to say that most people in most of the professions listed above are smarter than football players, but such is not the case. Some NFL players have posted terrific scores. Most famous for excelling is the Green Bay Packers’ Aaron Rodgers, probably the best quarterback in football today, who scored 35 back in 2005. The New York Giants’ Eli Manning, winner of two Super Bowls, scored 39 in 2004.

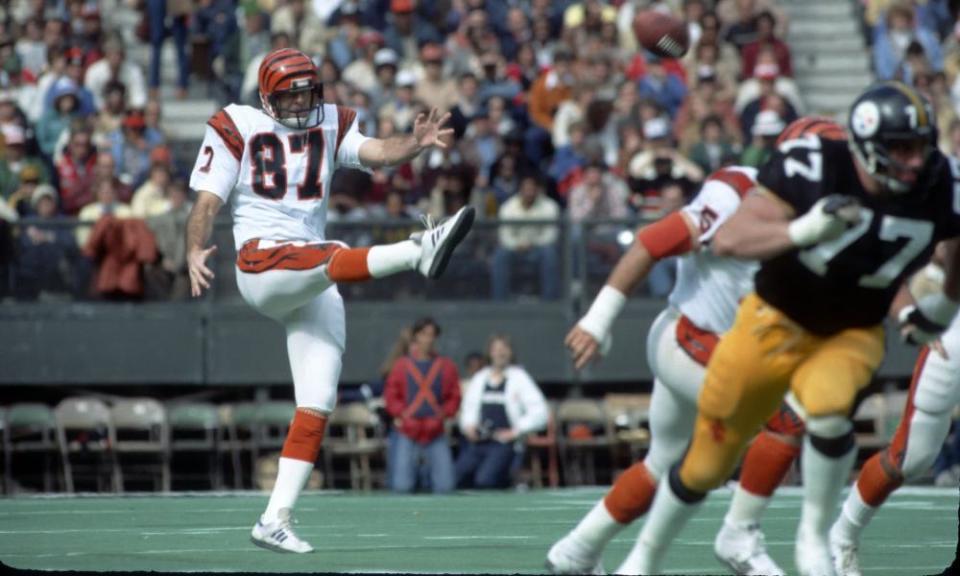

Receivers have just about the lowest average score, but future Hall of Fame receiver Calvin Johnson got 41 in 2007. Pat McInally, a punter-receiver who played for 10 seasons, posted a 50 in 1975, the only player known to have gotten a perfect score.

Wonderlic critics point out that the test scores aren’t indicative of success. The San Francisco 49ers’ Frank Gore, a rookie in 2005, scored an almost ridiculously anemic six but lasted in the NFL for 12 years.

Wonderlic’s lack of predictability causes many sportswriters to call for its retirement, at least from the NFL. In a 21 April piece on the site 12UP, Holden Walter-Warner noted that “Ryan Fitzpatrick records one of the best Wonderlic scores of all-time. That translated to a marginal starting career as an NFL quarterback, with just one strong year with the New York Jets.”

Well, yes, but perhaps the intelligence indicated in his Wonderlic score is the reason Fitzpatrick, a Harvard man, has been able to last 12 years with mostly terrible teams. And, for what it’s worth, in that one strong year with the Jets, the 2015 season, he set a team record for TD passes.

In a 2 March story for SI.com, Edward Krupat, director for the Center for evaluation at Harvard Medical School, wrote an insightful piece on how the Wonderlic has become an outdated method for gauging player intelligence.

When thinking about the combine and the NFL draft, I cannot help but see many parallels between the challenges faced by medical schools and pro sports teams in figuring out who will be a star and who will fall by the wayside. All of the students at Harvard have grades that go through the roof, just as the combine invitees have extraordinary athletic skills. But do they have those other factors that will help them become the next great surgeon? Do they have that other something that makes the more likely to become the next Peyton Manning rather than the next Ryan Leaf?

(For those who don’t know the story of Ryan Leaf, in 1998 there were two fabulous quarterback prospects whom everyone agreed had it all – size, smarts, and arm strength: Washington State’s Ryan Leaf and Tennessee’s Peyton Manning. There probably haven’t been two quarterbacks before or since who were more hotly debated going into the draft. The Indianapolis Colts had the first pick; the Arizona Cardinals had number two. The San Diego Chargers were so convinced that Leaf was a “can’t miss” that they traded three top draft picks and two players to acquire the second pick and, after the Colts took Peyton, chose Leaf, paying him an unprecedented $11.25m bonus. Manning, of course, became the most prolific passer in NFL history, playing 17 seasons and winning two Super Bowls, while Leaf played two horrendous seasons for the Chargers before being released. He started three games for the Cowboys and was out of the game at age 25. He subsequently did two prison stints for drug related felonies and was released in 2014. The sad fate of Ryan Leaf may prove that the New York Yankees great catcher Yogi Berra was right when he said, “90% of the game is half mental.”)

“What has struck me,” wrote Krupat, “in observing talent pools for Harvard Medical School and the NFL, is that regardless of how well they did in school, no matter what their IQ is, some candidates are really smart in ways that are unrelated to grades and tests. These ‘smart’ people become stars in their respective fields. Others just don’t have the sense that makes them successful practitioners of their art, whether on the football field on in the doctor’s office.”

Krupat’s goal is to create a metric by which one person in any field can be compared to another: “In medicine, this is an art and science that has made significant strides … in football, the gap between data that is meaningful and useful and data that is readily available is deep and wide.”

The Wonderlic test isn’t going to bridge that gap, ever, no matter how it’s refined. But it would be a mistake to throw it out the window because it isn’t perfect.

For their part, Wonderlic makes no extravagant claims for the test. “Given that teams are making million-dollar decisions,” says a Wonderlic PR rep, “with each draft pick, they should consider all the available indicators of a player’s abilities – mental and physical – and the Wonderlic test results are just a piece of that.”

As the late great Hall of Fame coach Bill Walsh told me years ago, “You can have one of two players who are about equal in talent. One of them is smart and the other is maybe not so smart. Which one you gonna pick?”