Peter Chiarelli and the problem with tunnel vision (Trending Topics)

(Ed. Note: We bring you Trending Topics on Saturday this week due to the NHL free-agent frenzy.)

It’s easy to become obsessed with something, and pick it apart.

Take, for example, an idea you hear about a lot at draft time: over-scouting. You really like a player, you see the obvious value he provides. But see him a few too many times and you start noticing things like, “He’s got a little hitch in his stride,” or “Well, his vision isn’t fantastic,” or “He didn’t back-check in this one game, so that might be an attitude problem.”

Familiarity breeds contempt in drafting, no two ways about it, just as the “seen him good” aspect of seeing a guy have a superlative game once can marry you to the idea that this is an elite-level player. If you get too hard a look at something, you start to see what it isn’t rather than what it is. And in evaluating the league’s great players — present or future — some GMs can very easily fall into this trap time and time again.

Peter Chiarelli is just such a GM. This is now the second time in just a few years that Chiarelli took a very, very hard ‘L’ in trading a top-two pick in the 2010 draft in pursuit of something he felt his team didn’t have or needed more of. And both times, it was because he allowed himself to dive down a rabbit hole of obsession after first getting a running start.

The Bruins lost the 2013 Stanley Cup Final, and Tyler Seguin had one goal on 70 shots in that playoff run. There were off-ice problems, too, but let’s not delude ourselves. We’ve all seen the Behind the B video: The Bruins traded Seguin because he didn’t score and didn’t particularly feel like anybody. In return for Seguin, who has gone on to rack up more than a point a game and 107 goals in three seasons with the Stars, the Bruins got Loui Eriksson (good player), Joe Morrow (who knows?), Reilly Smith (good enough, but already traded), and Matt Fraser (an AHLer). Boston also had to throw in a useful middle-six forward in Rich Peverley and now-non-prospect Ryan Button.

They got materially worse, and everyone without Black and Gold glasses on knew it day-of. But it was part of a broader Bruins trend that saw the club identify “being hard to play against” as the thing that got them to two Cup Finals in three years, with one big win. Not “having elite talent at three forward spots, a Hall of Fame defenseman, and two of the best goalies in recent memory.” You could see it in the absurd contracts extended to third-line guys (Chris Kelly had a $3 million AAV). And in chasing the toughness the team started down the path that would ultimately doom Chiarelli in Boston — he tried to pull out of the skid all too late — and lead the Bruins organization to continue chasing that dream with Don Sweeney as a Cam Neely puppet in the GM’s chair.

To that end, one could easily have made the argument at the time he was hired in Edmonton that Chiarelli had learned from his mistakes (he did try to get more skill on the roster in his final days in Boston) and would therefore be able to lead a super-talented Edmonton team out of the darkness. Now, though, we know the sad truth: Chiarelli learned nothing, but his focus on what makes teams successful in the NHL has moved marginally toward the rational.

Anyone could look at the Edmonton roster and say to themselves, “So much talent up front, but so little on the back end.” It was an obvious problem, and a more real one than Boston’s “lack of grit.”

But the same tendencies creep into the decision-making process, don’t they? If you have something you need, and you feel as though you have the means to fix it, then you fix it. Simple enough. But what the Oilers have effectively done is over-scout Hall, who is by any measure one of the three or four best players in the league at his position (in some order, it goes: Ovechkin, Benn, Marchand and Hall, though your mileage on each may vary), and found reasons to not-like him. The Edmonton media, after all, has been trying to get Hall out of town for a while now, and you can bet that just like all the smoke around the “No one likes PK in the Montreal room” rumors that circulated for years, it wasn’t coming from nowhere.

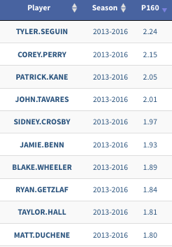

Management, it seems, just didn’t like what Taylor Hall brought to the table as a whole. And the things it didn’t like were so bad that it simply didn’t matter that this was part of what Hall brought to the table over the last three seasons:

That P1/60 column means “primary points per 60 minutes of play at 5-on-5” and that’s the top 10 in the league from 2013 to present. Goals and primary assists only, and Hall ranks ninth in the league among all players who have at least 3,000 full-strength minutes in that time. All those players around him are guys Chiarelli would kick someone down the stairs to acquire for the low, low price of a middle-pairing defender. Well, maybe not Tyler Seguin.

Now, again, Edmonton clearly needed defense, and preferably of the high-end variety, so Chiarelli went shopping. He apparently identified Adam Larsson, the No. 4 pick in 2011, as a guy he really wanted to shore up the blue line. Larsson may have some admirable qualities, but anyone who mistakes him for a clear No. 1 or 2 defender needs to get their eyes checked. Even beyond the eye test, which he doesn’t pass at that level of the sport, the underlying numbers are abysmal. And if you think that’s a product of his unfavorable usage in New Jersey (it’s not, but let’s pretend), in what way do you see that changing in Edmonton, where they still don’t even have a defender as good as Larsson’s former D partner Andy Greene?

In a rational universe, if the answer on the other end of the line for a one-for-one trade involving Taylor Hall is, “Adam Larsson,” you hang up so hard the phone explodes. Chiarelli is apparently no longer in a position to be rational, so desperate for blue line help has he become. Ray Shero saw a mark walking down the midway and decided this was an obvious opportunity to shoot for the moon with his ask. Leon Draisaitl? Jordan Eberle? Nah, let’s go for Hall. And inexplicably, it worked.

You have to admire the chutzpah behind that asking price; he ripped off Chiarelli for arguably the worst trade in terms of value in recent NHL history. Certainly, it’s the worst since the salary cap. That’s how wide the gap between Hall’s and Larsson’s on-ice contributions is.

And yeah, Larsson is signed for the extra year at a little more than $1.8 million less in AAV ($4.17 million for Larsson versus $6 million for Hall), but you might not even be getting what you pay for there. Certainly, you aren’t now.

In a lot of ways, too, it could be said that this trade was made to provide a little more of that famous Chiarelli fetish object: grit. It’s tough to justify trading an elite scorer who won’t even turn 25 until November. It’s tougher to do so and then say, “Well at least we signed a 28-year-old who’s notably worse and far less likely to deteriorate to replace him.”

Milan Lucic is a good player, but the only way in which you can reasonably compare him to Hall is by saying, “They are both NHL left wings.” Hall is on a different planet than Lucic in terms of quality, and that will continue to be the case for years, with a broadening disparity between them. And by the way, there goes the cap savings on Larsson-for-Hall.

Even after this trade, Chiarelli himself had to acknowledge that Larsson was not the answer to the Oilers’ needs on the back end. Pretty incredible expectation-setting, really. The team hopes Larsson becomes a No. 1 defenseman, and given that he’s only 23, there’s still room for growth. But Hall is arguably a not just a top-10 forward, but a top-20 player, period. How many defensemen would you take before Larsson? Right now, probably at least several dozen.

Maybe Chiarelli is hoping that acquiring blue liners in quantity rather than quality will distract from the fact that a team full of No. 3 defensemen still doesn’t have a No. 1 or 2. Maybe Hall’s act had somehow worn thin. But the Oilers, a team that is already heading into Year 3 of Rebuild 3, are somehow worse than they were after the draft.

And it’s all because they have a GM who gets so singularly focused on what he doesn’t have that he never appreciates what he does. At this point it’s a trend, because the habit followed him from Boston. At some point, you have to think it’s a handicap that proves he’s a guy who shouldn’t be running a team in the first place.

Ryan Lambert is a Puck Daddy columnist. His email is here and his Twitter is here.

All stats via Corsica unless otherwise stated.