Bowl fact vs. fallacy

The winner of the Motor City Bowl claims this shiny hardware.

(AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

Editor's note: This is the second in a two-part series examining the bowl system. Part I,

Dan Wetzel: The bowl boondoggle.

It was like watching pigeons fight over breadcrumbs.

Sixty-eight teams will play in 34 bowl games that start Saturday, and San Jose State and Florida Atlantic were desperate to be in the mix. How desperate? The Motor City Bowl needed a team, and the two schools swooned as if courting the The Granddaddy of Them All.

San Jose State, in a proposal certain to lose money, offered to take $250,000 and game tickets as payment to play in a contest that ranks right up there with its automotive cousin, the Meineke Car Care Bowl.

No dice.

Florida Atlantic agreed to forego cash and accept as compensation some 16,000 tickets, the majority of which will go unsold – for the right to spend the holidays in Detroit. Merry Christmas, Owl fans! Your team will be playing Central Michigan on Dec. 26 at Ford Field and your school will be scrambling to stay out of debt.

Yet in the world of college football, this deal does not qualify as insane. Fact collides with fallacy when it comes to common assumptions about bowl games and their often-cited benefits:

Do schools profit from bowls?

Last month, ESPN might as well have pulled up to the Bowl Championship Series headquarters in a Brinks truck. The cable network agreed to pay $500 million for the right to televise the BCS title game and three of the four other BCS bowl games for four years starting in 2011. Yet those astonishing dollar figures only further obscured a dirty little secret:

Even members of the so-called power conferences lose money playing in second-tier games such as the Motor City Bowl.

"We all know what the deal is," said Karl Benson, commissioner of the Western Athletic Conference. "It's the cost of doing business … Nobody's deceived."

Nobody but the general public, perhaps.

Figures on the NCAA's Web site report that the 29 non-BCS bowls generated $76 million last season, and the widely published bowl "payouts" indicate those games produced millions more. But those numbers are misleading for one primary reason: tickets are counted as revenue even when thousands go unsold.

“The good news is you get to go to the bowl game, and that's great. The heavy lifting comes when you're trying to make the numbers work.”

– Craig Angelos, athletic director at Florida Atlantic.

By its current formula, the NCAA's figures would indicate the Motor City Bowl has paid Florida Atlantic $750,000. To which anyone who learns the contractual terms might reply, "Are you serious?"

When schools such as San Jose State and Florida Atlantic are all but pleading for a spot in the postseason, bowls such as the Motor City can set the terms. This year the terms call for Florida Atlantic to accept precisely 16,666 tickets at an average face value of $45 apiece.

Craig Angelos, athletic director at Florida Atlantic, said he hoped the school could sell $100,000 worth of tickets – most of which will be distributed to inner-city programs in Detroit.

"The good news is you get to go to the bowl game, and that's great," said Angelos, one of many college athletic officials who believe the national exposure and extra practice afforded by even smaller bowl games outweighs the costs. "The heavy lifting comes when you're trying to make the numbers work."

In some cases, those numbers involve sleight of hand.

Case in point: The Humanitarian Bowl, which by contract pits schools from the WAC and the ACC, pledges about $250,000 a year toward the WAC in "sponsorship fees." No money exchanges hands. That's because the Humanitarian Bowl keeps the $250,000 as a "sponsorship fee," according to Benson, the conference commissioner.

Benson said the WAC paid more than $600,000 in those fees to bowls last year.

"What do you get in exchange? Nothing," he said. "Well, sometimes there might be a banner at a luncheon or a program ad or something like that."

Widely published figures show the New Mexico Bowl, the Hawaii Bowl and the Humanitarian Bowl – all three of which by contract take WAC teams – pay out a combined $4.5 million. Benson said his conference spent $1.6 million to send schools to those bowls but got no money in return.

The reason the WAC and other conferences can continue to survive without filing for bankruptcy is (sorry, playoff fans) the BCS.

This five marquee bowl games generate about $145 million a year, and all of the 119 teams classified as members of the Football Bowl Subdivision (formerly known as Division I-A) share in the revenue. That money covers the cost of playing in the lower-level bowl games – at least in theory.

Florida Atlantic is about to test that theory.

The Owls are members of the Sun Belt Conference, one of the five leagues that divvies up less than 20 percent of the revenue generated from the BCS games. Last year, the Sun Belt received less BCS money than any other conference.

On Thursday, Angelos still found himself punching numbers into a calculator and reviewing the ways in which he's trying to cut costs. Leave the school band behind and partner with a high school band in the Detroit area for a savings of $80,000. Depart at 1:30 a.m. the night after the football team plays in Michigan to save $10,000 on another night of hotel bills. Bring the six cheerleaders and school mascot shortly before the game because, well, it'll save a little more money.

While Angelos worked on the budget, Florida Atlantic coach Howard Schnellenberger worked with his football team in anticipation of its matchup with Central Michigan. The mere sight of Schnellenberger, with that famous white mustache and the national championship ring from his days coaching at the University of Miami, is enough to lift Angelos' spirits and remind him of the potential benefits.

Is extra practice time valuable?

Any day now, the boxes from the Motor City Bowl will arrive at Florida Atlantic's campus in Boca Raton, Fla. Someone will tear open the cardboard and deliver the contents to the players – a leather travel bag, a leather backpack, a bowl watch and a souvenir football – all embossed with the Motor City Bowl logo.

Estimated retail value: $489, just under the NCAA maximum allowance of $500 the players are allowed to receive in gifts from the bowl game. Schnellenberger and his coaching staff embraced another bowl gift courtesy of the NCAA – 15 extra days to practice.

Michigan coach Rich Rodriguez.

(AP Photo/Tony Ding, File)

It might be the one time in school history that the Michigan Wolverines coaching staff would view Florida Atlantic with envy. Actually, the feeling might be mutual.

Though the Wolverines failed to qualify for a bowl game for the first time in 33 years, they'll still take in $2 million from the Big Ten's share of BCS revenue. The Owls could desperately use that money, and the Wolverines could desperately use the extra practice.

The Wolverines finished 3-9 and struggled to grasp the new offensive system under coach Rich Rodriguez. They won't have a chance to work on it again until this spring because Michigan failed to make a bowl game and get a coach's favorite gift – extra practice.

"There may have been some other years where they could have afforded to miss a bowl game," said Gerry DiNardo, whose coaching career included stints at LSU, Vanderbilt and Indiana. "But this might be the worst year they could feel the impact of not going.

"Rich would have had another chance to implement his program and work with the younger guys. I'd say it's definitely another hurdle."

Gene Stallings, the retired coach who led Alabama to a national championship, downplayed the value of those extra 15 extra days of practice for little-used younger players. In explaining why, he cited the limit of 85 scholarships.

"With the limited number of players you have now, you play your guys," he said. "You redshirt some of them. But if most of the ones you redshirt were good enough to play, they'd be playing."

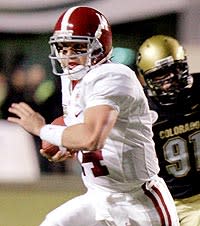

Alabama QB John Parker Wilson runs past Colorado defenders for a first down during the first quarter of the Independence Bowl in Shreveport, La., on Dec. 30, 2007.

(AP Photo/Rogelio V. Solis)

Yet Stallings said a bowl victory could propel a team into the following season, and Alabama fans certainly would agree based on what happened in 2007. A trip to the Independence Bowl last year might have seemed like an insult for those who have spent every waking moment awaiting the second coming of Bear Bryant. Worse yet, under first-year coach Nick Saban – whose $4 million a year salary drew almost as much attention as Bryant's Houndstooth hat once did – the Crimson Tide had lost their last four games of the regular season.

After beating Colorado 30-24 in the Independence Bowl, quarterback John Parker Wilson said of the victory, "It gives us great momentum heading into the offseason."

Talk about momentum. Though it's impossible to know how much can be attributed to its 15 days of practice leading up to a victory at the Independence Bowl, Alabama opened the 2008 with 12 straight wins before losing to Florida in the SEC championship game. The Crimson Tide, one year removed from the Independence Bowl, will face undefeated Utah in the Sugar Bowl.

Of course, there's also the case of Sylvester Croom and the Mississippi State team that defeated Central Florida in the 2007 Liberty Bowl. After being roundly hailed for leading the Bulldogs to their first bowl victory since 2000, Croom looked helpless when his team went 4-8 in 2007 and resigned after this season.

And anyone who thinks qualifying for a bowl game is enough for a coach to save his job should consider Glen Mason, who last coached at the University of Minnesota in 2006 and led the Gophers to seven bowls in 10 seasons. "I know there's a definite effect on your team when you win or lose that last football game," he said.

The effect when Mason's team blew a 31-point lead in the second half of the 2006 Insight Bowl and lost in overtime to Teas Tech? Mason got canned.

Schnellenberger is in no such danger. But the program could use a boost – the type for which Florida Atlantic and the Sun Belt are willing to pay.

Does TV exposure boost recruiting?

After the University of Louisville played in the 1999 Humanitarian Bowl in Boise, Idaho, athletic director Tom Jurich acknowledged the school had lost $193,000 from the trip and he admitted so without embarrassment.

Florida Atlantic coach Howard Schnellenberger is carried on his team's shoulders after defeating Memphis in the New Orleans Bowl on Dec. 21, 2007.

(Chris Graythen/Getty Images)

"We were looking for as much exposure as we could get and to reward our kids," he told the Louisville Courier-Journal. "You could have played in Egypt, and we would have been happy."

Happy because the game would have been televised, that is.

In an industry that covets visibility, Detroit doesn't seem so far from Boca Raton. The Owls already have some built-in visibility.

Schnellenberger's name is more recognizable than Florida Atlantic's logo. (In fact, Motor City Bowl executive director Ken Hoffman insisted Schnellenberger, not finances, was among the reasons Florida Atlantic got the bowl bid over San Jose State.) The question is whether blue-chip high school recruits will see something they like when Florida Atlantic plays Central Michigan in a game to be televised by ESPN.

And if those prospects do catch a glimpse of what Schnellenberger's selling, would they consider attending Florida Atlantic? In part because the Owls made it to the Motor City Bowl?

OK, so you haven't laughed so hard since you heard about the Poulan Weedeater Independence Bowl. But one of the reasons the Sun Belt is chipping in to pay Florida Atlantic's bowl costs is the national exposure. That, in turn, presumably boosts a program's stature, lures better players and in turn creates a stronger conference.

Last year the Sun Belt ranked 10th among the 11 conferences, ahead of only the MAC in the computer polls used for the BCS rankings. Based on the revenue-sharing formula the non-BCS conferences use, the higher-ranked conferences get more of the BCS money. So the Sun Belt is investing money to make money, and whether they will depends in part if Florida Atlantic can convert the exposure into recruiting top-notch players.

Might be too early to check the Rivals.com ratings, lest Owls fans tear out their hair and demand to know what the heck's wrong with this year's recruiting efforts. Currently, the Owls have one commitment – from Mike Flash, an offensive lineman. It's a lonely list compared to the one already compiled by Michigan.

“They're missing some leadership right now. They need some people that can take charge, and I feel that I can bring that in.”

– Michigan recruit Shavodrick Beaver.

Rivals.com currently ranks Michigan's tentative class seventh nationally, thanks to 21 players who have made verbal commitments. They include include two prized quarterbacks – Tate Forcier and Shavodrick Beaver, whose mobility appears well-suited for Michigan's spread offense. But Beaver's mother, Jackie, wondered whether her son might start scrambling while the Wolverines were getting clobbered week after week.

"I was like, 'OK, son. Are you sure that's what you want to do?'" she recalled.

Shavodrick Beaver chuckled at the memory and, unlike the Wolverines, said he "bounced back" from any trepidation about joining a program that missed out on a bowl game for the first time in more than three decades. Beaver said he frequently talks to others who have committed to Michigan, and apparently no one's defecting after hearing about the Owls' trip to the Motor City Bowl.

"They're missing some leadership right now," Beaver said. "They need some people that can take charge, and I feel that I can bring that in."

Spoken as if read straight from a recruiting pitch framed by a program trying to capitalize on not going to a bowl game.

"We're going to have more young players have an opportunity to contribute earlier in their careers than maybe four years down the road," Rodriguez said. "That's the truth."

Michigan's headway in recruiting despite missing a bowl is far less shocking than its record last season. After all, Notre Dame assembled a recruiting class considered the second best in the country after the Irish finished the 2007 season with a record of – sound familiar here? – 3-9.

The Notre Dame allure proved just as strong among bowl officials needing a team when the Irish finished 6-6 and were in a pool of at-large teams. In fact, Hoffman said he would have loved to have had the Fighting Irish, who opted for a spot in the Hawaii Bowl.

No hard feelings at the campus in Fort Lauderdale. When Angelos isn't looking at his budget numbers, he's looking past fallen powers such as Notre Dame and into a brave new future.

When's the big payday?

Boise State's breakthrough into the BCS and its upset of Oklahoma in 2007 paid dividends at the bank and in exposure.

(AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

If you thought Florida Atlantic's deal with the Motor City Bowl was crazy, wait until you hear this: Angelos said he thinks the trip to Detroit could move a step closer to "the big payday."

By that, he means a spot in a BCS bowl.

It would result in a $6 million payment to the Sun Belt Conference and more than cover costs for future trips to the Motor City Bowl.

Of the 53 non-BCS teams, only Utah, Hawaii and Boise State have qualified for "the big payday" by playing in one of the five marquee bowl games that generate the millions of dollars and entice schools to invest in the promise of that a small bowl one day leading to BCS riches, a pipedream that beckons like the arm of a slot machine.

But Angelos doesn't see the bowl game as a gamble, even with all of its crazy accounting and hard-to-measure benefits of extra practice and national exposure from a second-tier bowl that like many others will end up costing money.

"I look at it that we're paying our dues to move this program forward," Angelos said. "And if we have to foot some of the (bowl) costs, that's the way we'll do it."