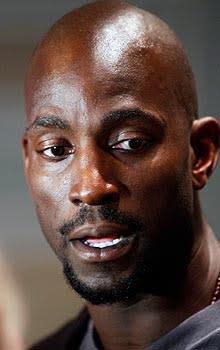

Garnett makes stand in NBA's labor battle

Thirteen years ago, Kevin Garnett(notes) was the perfect target for the commissioner and the owners: the $126 million man. The NBA had gone to labor war over his contract, turning him into a talking point of the salary-cap crusade. Here was a star who embraced life in a cold-climate small market, who never pined for the bright lights, the big city. He made the Minnesota Timberwolves relevant, a contender, and they haven't played an important basketball game since trading him.

He's 35 years old, on a bad knee, and near the end of a Hall of Fame career. And yes, it takes some guts for Garnett to stand there in these Players Association news conferences, strong, defiant, and take the arrows again. He's made more than $200 million in his career, and there are no more big contracts awaiting him. The Boston Celtics have one more season to make another title run, and then, with Garnett and Ray Allen(notes) free agents, the team will probably start to rebuild again.

For Garnett to privately fight for the union in meetings, to implore the players to make no more undue concessions even if it means they sit out the season, has to be one of the most unselfish acts in these labor talks. They'll call him greedy, ungrateful, a pig, and they'll be wrong. There's no winning for Garnett in this labor fight, unless he's left something for the next generation of players, the way his predecessors did for him.

"What he's doing now, to me, it says a lot about K.G.," says a younger NBA player who made about $5 million last season. "He's willing to sit out the year, and give up [$21 million] at the end of his last big contract, and probably his last really good chance to win another ring. For him, this is about the principle.

"I don't want to hear this stuff from our guys saying, 'Oh, he can afford to sit out. He's made a lot of money.' I respect the [expletive] out of those guys standing up for us right now, him, Kobe, all of them."

[Related: Union urges NBA players to not back down]

This isn't nobility. This doesn't make Garnett a social worker, a teacher working for low pay in an urban school, a missionary in famine-stricken Africa. He doesn't deserve a standing ovation, nor a parade, nor much beyond this simple fact: He doesn't need to apologize for fighting for his side in this dispute.

The NBA owners never wanted to go north of 48.5 percent for the players' share of the basketball-related income (BRI), league sources say, and commissioner David Stern had lean support when he pushed the most recent offer to 50 percent. There hasn't been one source in ownership, in management, who believes the players will get that offer again – at least no time soon. Now, the union has boxed itself in with declarations it won't go that far to get a deal with the owners, so there's a real chance these two sides are hunkered down again.

Truth be told, the commissioner probably pushed his owners as far as they're willing to go now – to really try to end this lockout – and it didn't happen.

Perhaps eventually, the players will make more concessions, and this deal will get done. Nevertheless, Garnett, Kobe Bryant(notes), LeBron James(notes), Dwyane Wade(notes) – all of them – are justified to call the league's bluff on these concessions. Superstars have long made the NBA, and long driven the economics of the sport. It's hard to deny the immense value that Garnett himself brought to the Wolves and, now, the Celtics, where all he did was return the glory, the profitable standing, of the NBA's most historic franchise.

When the Wolves had little else, they had Garnett. He covered for a bad owner, and a mediocre front office. When Glen Taylor was pinched for a secret contract with Joe Smith(notes), the Wolves paid a steep price in Garnett's prime. He never demanded a trade, never asked out. In good times and bad, Garnett was a franchise player. He understood the burden of it: Even when it wasn't easy, K.G. knew that he was paid to carry it all.

[Related: Stern sets deadline to save start of NBA's regular season]

He was the reason those Wolves sold out games, the reason they made the playoffs, the reason they had relevancy in the NBA. Once he left, the Wolves fell apart. Taylor hired an unqualified general manager, David Kahn, to run the franchise, and the Wolves kept slipping further and further. Small markets have a tiny margin for error, and Taylor obliterated it.

Only in this twisted NBA ownership culture, could Taylor – who lorded over what Stern declared was "one of the most far-reaching frauds we've seen" in the Smith scandal – become the chairman of the NBA's board of governors.

When Taylor got busted in 2000, everyone expected Garnett to start working on his exit strategy. It never happened until 2007, when the Wolves were ready to move him and rebuild again.

"It's very, very easy to jump ship when things get hard," Garnett said. ''It's very, very easy to start thinking differently. I'm not that type of person."

Now, it's the end of the line in 2011, and there was Garnett in the private players meeting on Tuesday in New York, screaming to his peers. "Apoplectic," one source said. K.G. screamed that the players owed it to the next generation to stand firm, to concede no more to the owners in these talks. He had everything to lose – his $21 million for the year, his last chance at a championship with Boston – and still he keeps fighting for something here. When the NBA had its biggest member meeting in New York prior to the start of the lockout, it was Garnett delivering the most riveting, most emotional speech of this saga. It may not be what you believe in – or believe is justified or fair – but all these years later, when this labor fight didn't have to be about K.G., he's still willing to take the hits for it.

It doesn't make him a hero, a martyr, or anything of the sort. With K.G., though, you know where he stands. Give Kevin Garnett that, anyway. You know where the man stands.

Other popular stories on Yahoo! Sports:

• ESPN, Hank Williams Jr. have differing views on his departure

• Ravens' Michael Oher asks: Who was Steve Jobs?

• Athletes with foreclosed homes