Ye old ball game

|

WESTFIELD, Mass. – For his latest muse, Jim Bouton traveled back, back, back, beyond the warning track of the modern era, through the Field of Dreams cornfield and into the 19th century to a place far different from the dysfunctional clubhouse he chronicled as a fading knuckleball pitcher in his seminal insider revelation, "Ball Four."

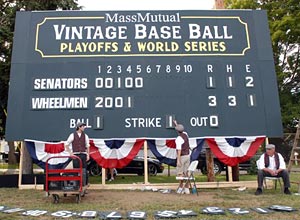

On a quaint patch of green in this historic western Massachusetts town last weekend, Bouton's vision of recreating an authentic 1880s ballgame amid a theatrical set piece of the period sprang to life at the first Vintage Base Ball Federation World Series.

Upon reaching the field, spectators passed a kid in a newsboy cap and suspenders hawking programs, a banjo player singing "In the Good Old Summertime," Keystone Cops giving passersby a flippant once-over, and a legion of primly dressed women holding signs demanding their right to vote. By then it was only a slight shock to come upon a thoroughly ordinary diamond populated by thoroughly distinctive players wearing tiny gloves and pillbox caps. A man with a handlebar mustache wielding a thick-handled bat politely informed a cigar-chomping umpire that given the choice, sir, he'd like the strike zone from the shoulders to the belt, please, rather than from the belt to the knees.

Then came the pitch and the familiar thwack! of wood against cowhide, and it was no different than any game at any point since baseball was invented, who knows precisely how long ago. There were hits, runs and errors. Actually, a lot of each, primarily because those diminutive gloves are more appropriate for plucking weeds than ground balls.

|

Many truths unfold watching Vintage Base Ball, including the realization that the most common 19th-century injuries weren't strained oblique muscles or torn rotator cuffs, but chronically swollen paws and dislocated fingers. Bouton, the VBBF commissioner and a born showman who can turn out vintage spin on demand, wouldn't have it any other way.

"In today's game, people expect every play to be made and get upset when there is an error," he said, eating a Creamsicle as a crowd of about 2,500 cheered the action in the afternoon sun. "In Vintage Base Ball, nobody expects a play to be made and everybody is thrilled when it happens."

Bouton, 68, dapper in a white shirt, red suspenders and bowler, is no ivory tower administrator. He seemed to be everywhere at once, exhorting the crowd through an enormous megaphone (no electricity allowed, of course), playing straight man to a mime and signing copies of "Ball Four" and other books he wrote.

When a nurse attended to a spectator who'd been hit in the side of the head by a foul ball, Bouton grabbed a large umbrella that had been set up to shade ticket-takers, pulled it from the ground and planted it next to the fallen man. Meanwhile, a player discreetly retrieved the ball because of a policy true to the period – no new ball unless one is irretrievably lost.

As for the playing rules, Bouton and his board of directors of renowned baseball historians and writers have cherry-picked from 1850 to 1890 the ones they believe make for the best spectator sport. Besides the batter's choice of a high or low strike zone, other rules that no longer exist include: A foul ball caught on one hop is an out; there are no balks or timeouts; the hidden-ball trick and quick pitches are allowed at all times; and if the lone umpire can't see a play, he may "appeal to the bystanders and render his decision according to the fairest testimony at command."

Interactivity, it seems, was popular long before the Internet.

|

"All rules are a function of context, and today some seem silly and some seem quaint," said John Thorn, a prominent baseball historian and author who serves on Bouton's board.

"But they made sense in their context. The game was gradually systemized, and it's always improving. Different baseball was played by different rules in different places, and the game evolved by amalgamation and drift."

To catch Bouton's drift is to realize he is more pragmatist than purist, and what else could be expected from the man who transformed the way major league baseball was perceived when he wrote "Ball Four" in 1970? He has been an entrepreneur since giving up the knuckleball and helping create the faux-chaw bubble gum "Big League Chew" in the late 1970s.

He envisions Vintage teams "popping up like mushrooms" and it becoming a lucrative business. Bouton says there are about 200 Vintage teams around the country, most playing a handful of games each year. The four World Series teams – the Hartford (Conn.) Senators, Westfield Wheelmen, Amador County (Calif.) Crushers and Sheridan (Mich.) Stars – qualified by paying a $500 fee and winning regional tournaments.

Bouton has launched a vigorous fundraising campaign to develop a $15-million, 19th century replica ballpark in Westfield that he says would be "a visual feast for television producers, assignment editors and art directors."

|

This populist approach offends some folks affiliated with the separate Vintage Base Ball Association, which first gathered in 1996 in Columbus, Ohio, to commemorate the earliest recorded amateur match. Sticklers for historical accuracy, they convene every year, playing under the earliest rules codified by Henry Chadwick in his 1860 compendium of the game, "Beadle's Dime Base-Ball Player." The primary differences are that the ball is softer, pitchers toss it underhand and no gloves are used.

Thorn, who has been involved with Vintage Base Ball since umpiring games in New York and Massachusetts 20 years ago, has advised the VBBA as well as the VBBF, and aligns himself closer to Bouton.

"There is some friction between the groups," he said. "By and large, everybody understands that the success of one is good for everybody. When there is zealotry and people think there is only one way, the whole thing becomes tedious."

Said Bouton: "For us, Vintage Base Ball is a blend of theater and unscripted sports competition, which makes it different than, say, a Civil War battle re-enactment. We are capturing the spirit of a time. And we are playing some pretty good baseball."

Ever the huckster, he turns the bickering on its head, saying it adds to the authenticity.

"The arguments are historically correct because they were doing the same thing back then," he said. "The rules were in a state of flux between 1850 and about 1900. Those wanting to improve the game always had to fight the purists."

Probably only a handful of the fans watching the World Series cared about such particulars. They paid $10 admission to step back in time and watch a doubleheader on the last day that would determine a champion.

|

"This is as much fun as I've had in a long while," said Marcia Rogers, a lifelong Westfield resident who learned about the Vintage Base Ball World Series through a presentation made at the local library by the captain of the Westfield Wheelmen, Dan Genovese.

"There's so much going on in the stands, everyone is enjoying themselves and the baseball is good too. This is going to become a tradition here."

For the record, Hartford scored 13 unanswered runs in the last three innings to defeat Westfield in the finale of the four-day tournament. It was the second victory of the day for the Senators, who dispatched Amador County, 20-7, to advance to the final.

As for the men under the pillbox caps, the stories behind their participation were as interesting as the games themselves. All the players have nicknames in the spirit of the 19th century. Meet a few:

• Scott "Stretch" Welch is an outfielder with the Crushers, the California team that qualified by winning a four-team league in its bucolic home area near Lake Tahoe and taking a playoff series against the winner of a Bay Area league.

Stretch is a diehard Boston Red Sox fan with a tattoo on his shoulder to prove it. So, with Westfield being tantalizingly close to Fenway Park &which he'd never visited – he and six teammates rented a van and drove 90 miles on the Massachusetts Turnpike for a Red Sox game against the Los Angeles Angels that began at 1:20 p.m. The Crushers had a World Series round-robin game at 5 p.m., so it was a tight squeeze for Stretch, who bought a ticket from a scalper for $140, sat through 1 2/3 unforgettable innings a few rows from the field, took a ton of photos, then gathered up his pals – who were immersed in the lively scene outside Fenway – and made it back just in time for their own game.

|

"I saw Papi hit a bomb, it was the greatest experience ever," Stretch said of Red Sox slugger David Ortiz. "I would have paid $500 for that ticket."

• Mike "Goose" Carey, the superintendent of schools in Amador County, launched Vintage Base Ball in the area after searching online for an old baseball uniform to wear while he recited "Casey at the Bat" at school assemblies.

"I played men's baseball and a lot of softball, but this sounded so cool," he said. "I found Jim Bouton and he helped me put a league together."

Now there are four Vintage teams sprinkled in the Gold Rush towns of Sutter's Creek, Jackson, Pioneer and Ione. In addition to a league schedule, they've played exhibitions at minor league ballparks in Sacramento, Fresno and Stockton.

Most people associate the beginning of baseball with the Northeast, but the game flourished in Northern California at the time of the Gold Rush. The town of Mudville in Ernest Thayer's "Casey at the Bat" probably was Stockton, Goose said.

"The two players referred to in the poem before Casey (Flynn and Jimmy Blake) played for Stockton in 1887," he said.

Alexander Cartwright, who some historians believe wrote the first rulebook in 1845, came to Gold Country looking for his fortune in 1849, although he didn't last a year. Still, it tickles Goose. "We have a connection with the origin of baseball," he said.

|

The 60-ish Goose was the oldest player in the World Series, and the dugout came to life when he stepped to the plate for his only at-bat against Hartford. His teammates chanted, "Goose, Goose, Goose," as the pitcher went into his windup. The crowd got into it too, and when he banged a sharp ground ball up the middle for an RBI single, everyone stood and cheered.

• Chris "Grit" Moran caught all 16 innings of the final-day doubleheader for Hartford, wearing a mitt the size of a flyswatter and sporting a left index finger swollen to the size of one of the dill pickles hawked in the stands. A talented player who bears a passing resemblance to Crash Davis from the movie "Bull Durham," Grit hardly had to chase a pitch to the backstop all day.

"Back then, the catcher stood and had to decide whether to play a pitch on one hop or on the fly," Grit said. "I have to last nine innings, so I've learned to catch a lot differently. It's like absorbing a punch."

Want to start a Vintage team? Grit will visit your town and give a tutorial. He'll explain that the term "hitting one back to the box" originated before mounds and rubbers, when a pitcher only had to remain within a 4-foot-wide by 6-foot-long box when delivering the ball.

• David "Fleetwood" Chambers was the Hartford first baseman and the only African-American player in the World Series, which apparently was an authentic standing. According to several publications, the first black professional player was Moses "Fleetwood" Walker, who played 42 games in 1884 for the Toledo Blue Stockings of the American Association, batting .263. His brother, Welday Walker, played in a handful of games.

|

Early in the semifinal game against Amador County, a play involving Fleetwood illustrated the gamesmanship of Vintage Base Ball, the uneasy truce with the lone umpire and, ultimately, the triumph of competitiveness over gallantry.

He tried to advance from second to third on a play at the plate, and the catcher's throw seemed in time. However, the third baseman dropped the ball trying to make the tag, then swiftly picked it up and hid it under the loose bag. Had Fleetwood wandered off the bag, he could have been the victim of a perfectly legal hidden-ball trick.

Fleetwood, however, sensed something amiss and remained on the bag. Meanwhile, the umpire, stationed near home plate, called him out because he hadn't seen the ball drop during the tag. The Senators protested and the umpire asked the third baseman if he had, indeed, made a legal tag. On a different day, under different circumstances, perhaps he would have fessed up. But with his team already trailing 9-0, he didn't, and the inning was over.

• Wheelmen catcher Dan "Gunner" Genovese has written two books about the history of the game in the area, although his gnarled fingers must be a major impediment when typing.

Gunner also gives presentations about Vintage Base Ball like the one at the library attended by Marcia Rogers and her husband of 47 years, Jim. They were so taken by the concept that they were seated behind home plate for the World Series final.

"It's a wonderful period piece, part historical lessons, part competition," Jim said.

The sense of history is awe-inspiring, huh?

"Well, actually," Marcia said, her smile revealing the slightest touch of New England snobbery, "we celebrated our town tri-centennial in 1976, so 1880 wasn't so long ago."

|

Baseball, though, was in its formative stage, balancing the social activity of gentlemen and the cutthroat competition of ruffians. Bouton's federation leans toward decorum, prohibiting cursing, showboating and taunting.

He likes to imagine that's the way it was, even if it wasn't.

"Our game requires the players to behave, it offers a lesson in old-fashioned sportsmanship," Bouton said. "It's just honest-to-goodness baseball."

And no small amount of 19th-century theater, to the end. When the Senators defeated the Wheelmen for the championship, the teams gathered at home plate and gave each other a rousing, "Hip, hip, Huzzah!"

Within minutes, the players were slugging Gatorade, talking on cell phones and hopping into their cars. Somewhere, Barry Bonds was taking a mighty swing.

The time warp was over. Vintage Base Ball, though, might have only gotten started. The man who four decades ago changed the way Major League Baseball was perceived by writing a book now plans to script the game's turn through the pages of history.

"Who wouldn't want to have this much fun?" Bouton said. "Who wouldn't want to do this again?"