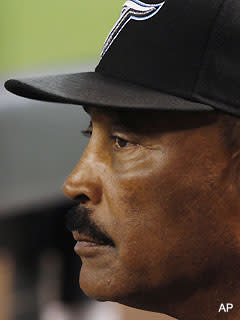

Taking a closer look at Cito Gaston, baseball's mystery manager

Ready those fake mustaches, folks. After 46 years in professional baseball Cito Gaston is set to fill out his last lineup card of his career on Sunday.

Despite that longevity, Gaston spent most of his years affiliated with just two cities — Atlanta and Toronto. The Braves were the club that drafted him in 1964 and gave him his first cup of coffee in September 1967, before bringing hime back from 1975 to 1978. It was in Atlanta that he met the two men who had perhaps the most profound effect on the next five decades of his career: Henry Aaron, who roomed with him and took him under his wing, and Bobby Cox, who gave him his first major league coaching job in Toronto.

Gaston didn't play with either man very long — just nine games as Aaron's teammate in 1967 and just 60 games before Cox released him in 1978 — but both made a lasting impression on him.

He would go on to win as many World Championships as both men combined.

Gaston's playing career was mostly undistinguished. After his brief stint in 1967, he went back to the minors, where he was selected by the Padres in the 1968 expansion draft, their last of 30 picks. He managed a brilliant, flukish All-Star campaign in 1970, hitting .318 with 29 homers and establishing career-highs in virtually everything, including games played. But he never reached those heights again. (The year was so out of character for the platoon outfielder — who only reached double digits in homers on two other occasions, and never again hit .300 — that Matt Klaassen compares Gaston's 1970 to Jose Bautista's(notes) 2010.)

Gaston retired in 1978, two games after the Braves released him. And once again, his career was shaped by Aaron and Cox. In 1981, Aaron helped him find a job with the Braves as a minor league hitting instructor. The following year, he came to Toronto as Cox's hitting coach. He effectively never left. He was the Jays' hitting coach until 1989, when he took over as manager from the fired Jimy Williams. He missed a month of the season in 1991 while recovering from back surgery, but otherwise he managed the team till he was fired in 1997, served as hitting coach again from 1999-2001, and then was hired in 2002 as a special assistant to the CEO. His second managerial stint began in 2008 the way the first had, as a midseason replacement, and it produced much the same result: a flurry of wins, exceeding the previous year's total despite the slow start.

He has been dogged by a number of critiques during both managerial stints. The first issue was a too-passive style as manager. Not only did columnists often criticize him, but ESPN reported in 2009 that "at least 50 percent of Toronto's players believed problems existed with the manager." Typical was a comment by Lyle Overbay(notes):

"[Gaston] never really said a lot. As we were winning, he was kind of sitting on the back burner."

His silence applied to his in-game tactics as well. As Chris Jaffe writes in his book "Evaluating Baseball's Managers," he was "the ultimate minimalist" whose teams were frequently last in bunts, in pinch hits, and in relief pitchers. Bill James described his managerial style as "inert."

The other persistent complaint was that he was too slow at working young talent into his lineup. ESPN analyst and former Toronto executive Keith Law just said "it's ridiculous" that Gaston didn't play young stars like J.P. Arencibia(notes) and Travis Snider(notes) more often. Similar complaints were raised before his 1997 dismissal, when he was criticized for not giving more playing time to young stars Shawn Green and Carlos Delgado(notes). For all of the warm memories and gratitude being expressed at his retirement, few in Toronto are actively clamoring for him to stay on. Instead, blogs like Drunk Jays Fans have written things like:

"No more Cito. The last thing we need is Travis Snider playing three games a week and J.P. Arencibia playing back up catcher next year."

Gaston will retire just north of 890 wins and with two World Series rings (won in 1992 and '93), numbers that make him 65th and 22nd, respectively, on the all-time register of managers. (Many have written that he has over 900 wins, crediting him with the games the team won while Gaston recovered from back surgery and Gene Tenace was interim manager. Baseball-Reference.com records his total as 892 heading into the weekend.)

Race also defined much of his career. By my count, he is just the 15th African-American manager in history and just the third to win more than 800 games (along with Dusty Baker and Frank Robinson). He's the only one to win a World Series.

Gaston's hiring in 1989 marked only the third time an African-American was hired as a manager and it came two years after Dodger GM Al Campanis caused a stir by saying that African-Americans "may not have some of the necessities to be, let's say, a field manager, or, perhaps, a general manager." His firing in 1997 came shortly after he suggested that certain journalists who had criticized him would not have "(taken) the same shot at me if I was white."

During his 11-year hiatus from the manager's chair — unprecedented among managers who have won multiple World Series — Gaston interviewed for some job openings and then finally stopped, believing that he was being tokenized and not taken seriously as a candidate. It's impossible to know whether unconscious or overt racism kept him from managing, but it's hard to rule it out completely.

Because of his passive managerial style and his general taciturnity — "he'll give you the impression that he was little more than a bystander while the Blue Jays were marching into the history books," wrote Walter Leavy in Ebony — few writers have been able to figure out exactly what he did well as a manager, though his .516 winning percentage, his four division championships, and back-to-back World Series rings suggest he must have been doing plenty of things right. Yet despite all the criticism he's weathered, nearly all of the franchise's brightest moments have occurred with Gaston as field manager: Four of the five division titles, both of the pennants and both of the championships, two of the four Cy Young Awards (Pat Hentgen in 1996 and Roger Clemens in 1997), and the debuts of five of the best players in franchise history: Hentgen, Delgado, John Olerud, Juan Guzman and Roberto Alomar.

Though Joe Carter, Roy Halladay(notes) and others make good arguments, Gaston is the face of Canadian baseball, the man who presided over the majority of the most memorable moments in the history of MLB in Canada. (The Expos had their share of memorable moments, including the Hall of Fame careers of Gary Carter and Andre Dawson, but their 2004 departure to Washington casts a cloud over much of that history.)

In their grudging but heartfelt sendoff, Drunk Jays Fans managed to praise the man whom they'd scourged so often before in the past:

Even this year —say what you will about many of his decisions (and believe me, I have) — Cito has demonstrated his skill and his value as a manager and a teacher, helping Jose Bautista adjust his swing, taking a hands-off approach with the starting pitchers, and guiding an exciting, overachieving ballclub. [...]

Cito, while we may have disagreed with you — a lot — and we may have sometimes been too quick to criticize and too reluctant to praise your efforts, we thank you for all the memories, and we wish you nothing but the best.

Gaston's success may have been mixed with some down times, but it also was no accident. He was an All-Star and a World Series winner, and if he never again reached the heights of his sharp peak, few of his peers, or mentors, ever reached those heights at all. (Bobby Cox will likely retire with just one championship, and his playing career ended after two brief seasons; Henry Aaron retired without ever having been asked to manage.)

Gaston won't enter the Hall of Fame, and his retirement has been largely overshadowed by the departures of Cox and Joe Torre. But he has had a remarkable career, much like his retiring peer Lou Piniella, another All-Star platoon outfielder who became a championship manager. It has been a good 46 years for Clarence Edwin Gaston, and a good 28 years for Toronto to have employed his services. Few second acts are as triumphant as Gaston's, as he finally received a chance to retire on his own terms.

Thanks for the mustache, Cito.

And the memories, too.